The Work of George Wendt

Notes on the life and times of the late George Wendt, an actor with some size on him

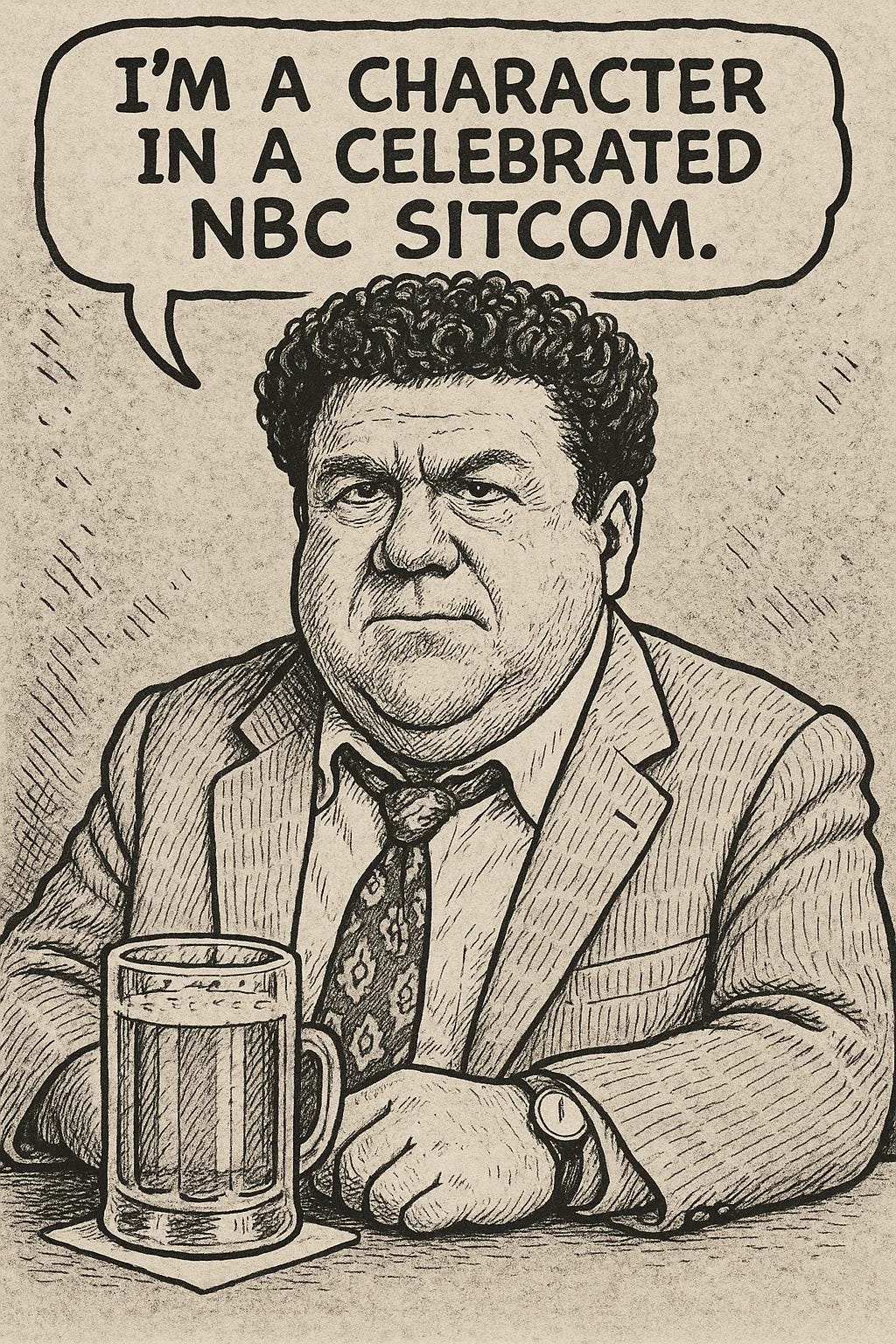

George Wendt died yesterday at the age of 76. The big man who sat on that corner barstool for 11 seasons played a character of quiet truth that America understood immediately. Norm Peterson was the working stiff who needed a seat at the bar more than he needed the beer. We saw our sad, intelligent uncles in him. We saw the fathers of our friends who carried a paunch and wore their disappointments without letting them define their lives.

When Wendt entered the bar on Cheers, the chorus of “Norm!” rang out and he belonged there. The rest of his character’s shitty life dissolved. The failing marriage, the white-collar accounting job he approached like an out-of-place blue-collar lout by avoiding it, the insecurities about his weight — all vanished in the warming comfort of a place where everybody knew his name.

Television creates mythologies out of our common experiences. Wendt's performance became legendary because his portrait of regular life came without judgment. This is what made Norm transcendent. He wasn't a punchline about a fat guy drinking beer. He was a complete soul wrapped in ill-fitting button-down shirts and expanding waistbands.

Wendt came from Chicago's South Side, where the children of immigrants crafted lives out of Midwest pragmatism and union paychecks. It wasn't a place for pretension. The factories and stockyards were too close, the reality too present for anyone to put on airs. His grandfather was German, the rest of his ancestry mainly Irish. The Midwest makes such combinations all the time, churning people of different origins into something distinctly American. In any event, he was Catholic, which meant his Harvard was in South Bend, Indiana.

Notre Dame didn't work out for him. He failed spectacularly there, earning a 0.0 GPA before moving on to the Jesuit-run Rockhurst College, where he eventually graduated. America loves a slow starter who finds his true calling after stumbling around. Wendt found that calling at Second City in Chicago, a comedy institution where he started by sweeping floors.

Second City became his real education. He watched performers create characters through tiny truths. He absorbed the rhythms of good acting without the formal training. Then he applied what he learned, climbing from stagehand to featured performer through the late 1970s. That journey shaped his ability to create lived-in characters without visible technique. His performances never showed the machinery underneath.

This lack of visible technique defined Wendt's portrayal of Norm. Every movement seemed natural, every response genuine. The writers gave him memorable one-liners, but his delivery made them sound like things a person like him might actually say. There was an authenticity in his physical presence that couldn't be faked.

Cheers started slowly in the ratings. The network kept it alive despite poor numbers and the bleakness of the inner lives of many of its unattractive barfly characters, a patience almost unimaginable in today's television landscape. Wendt kept showing up, holding down that barstool, delivering those lines. Then The Cosby Show arrived and pulled Cheers into the light with it. America found Norm Peterson and recognized him immediately.

The most profound thing about Norm was his contentment with his station. He didn't scheme for greatness like Ralph Kramden or Fred Flinstone. He accepted his life with a working-class stoicism that feels increasingly foreign in our ambition-obsessed culture. He found a degree of pleasure in simple moments — a cold beer, a good joke, the company of friends who slapped his back and busted his balls.

Wendt's other defining role came on Saturday Night Live as superfan Bob Swerski on the "Da Bears" sketches. Again, he embodied a particular Midwestern type — Bob Swerski in wrap-around shades, mustache bristling, vowels heavier than Polish sausage. Wendt was reporting on his Chicagoland kin, not mocking them. The flutter of his sunglasses when Super Bowl-winning coach Mike Ditka’s holy name is invoked is pure reverence. He turned what could’ve been a one-note joke into folk art rooted in genuine love.

That was his secret: Wendt never looked down on characters like these. He inhabited them with understanding, showing their humanity beneath the broad comedy. Their thick accents and unwavering loyalty represented a city that identifies through its teams, and their obsession with Bears coach and Pitt Panthers football legend Ditka (actually the half-Slovak, half-German embodiment of late 1950s Pittsburgh sporting culture against whom my own father had played high school and college football) hit close to home.

In the literal sense, Wendt’s work hit closest to home for me with Gung Ho, Ron Howard’s half-decent 1986 Rust Belt comedy about a fictional Pennsylvania auto plant bought by a Japanese firm. Wendt’s put-upon, demoted-to-janitor assembly line worker Buster isn’t the lead — that honor would go to Pittsburgh’s own Michael Keaton, yet to don the Beetlejuice makeup or Batman suit for Tim Burton — yet the film’s soul lives in his crestfallen look when the assembly line falters in its bid to produce 15,000 cars in a month. In the words of the late Roger Ebert, Wendt serves as the “proletarian mirror” for everyone whose mortgage depended on a time clock.

These performances land differently for those of us who grew up in the Midwest. We saw our relatives represented without mockery. Those fat, shrewd uncles with their expanding waistlines who could fix anything but couldn't fix themselves. Those friends of our fathers who came over to watch games and spoke primarily in grunts and nods. The men whose stunted emotional lives remained hidden as they struggled through what’s left of a changing world that was soon to look nothing like the world of their own fathers.

Television trades in types: lovable lout with a harridan of a hotwife, schlubby horndog neighbor in a Hawaiian shirt, fat guy in a little coat. Wendt kept gliding past the template. Cast him as the sloppy buddy, he lets a solitary blink hint at community-college ambitions abandoned for shift work. Cast him as harmless backdrop, he speaks a line that lands like moral ballast. Writers noticed, feeding him stray jokes about art or politics, trusting he could tuck them into the easygoing shuffle without rupture.

Regardless of his circumstances, exhaustion always wrapped Wendt like a second coat. Corduroy elbows shine from wear, tie loosened but presentable. He is not slovenly; he is spent. Factories, insurance cubicles, and family obligations mildew bodies not built for treadmills. Wendt carries that fatigue without self-pity.

The serious obituaries will focus on his six Emmy nominations, his 11 years on a beloved sitcom, and his 170 other film and TV credits. They'll mention his marriage to Bernadette Birkett, who voiced Norm's never-seen wife Vera. They'll list his roles and quote his famous lines. But they might miss what made Wendt special — his ability to represent ordinary life with extraordinary truth.

Wendt once said he felt similarities with Norm but was happier and more ambitious. This makes sense. It takes tremendous drive to succeed in entertainment, to move from sweeping floors at Second City to becoming a household name. The gap between actor and character reveals Wendt's skill. He understood Norm's contentment while possessing a kind of hunger that big Norm lacked.

For many men of size, Wendt's success offered hope. Here was a 300-pounder who became famous not despite his body but partially because of it. He didn't try to hide his weight or transform himself to meet Hollywood standards. Yet he also didn’t have to throw himself into tables and chairs like the tragic Fatty Arbuckle or the even more tragic Chris Farley. He performed with conviction and let his physical presence merely serve as part of his art.

John Goodman may have been the more versatile blue-collar actor, stretching across more varied roles with greater range. But Wendt perfected something equally valuable — the art of embodying a specific type of American man with complete authenticity. He showed us the dignity in ordinariness, the heroism in showing up, the value in being exactly who you are.

Somewhere today, in bars across America, day-drinking alcoholics are nursing lawnmower beers, making occasional observations that their friends find amusing. They aren't trying to be noticed. They're just trying to exist in clean and reasonably well-lit spaces around people who tolerate them. George Wendt showed us their worth. For that alone, even teetotalers like me should raise our glasses. Norm would appreciate the gesture, though he'd make a self-deprecating joke about it: “It’s a dog-eat-dog world and I’m wearing Milk-Bone underwear.”

This is so good.

Another good piece. Interesting the various elements of the piece that resonate for us commenters, says this son of working class immigrants who was also raised on the south side (and who remembers the occasional smell of the Stockyards...) and who encountered many Norms of that time (a loooong time ago, though).