The Work of Autoandrophilia

On the men who are transforming themselves into the men they lust after

Editor’s note: I'm publishing this long article today in preparation for my appearance on ’s podcast tomorrow,1 where we'll be discussing autoandrophilia and my broader work examining masculine identity transformation. Among other things, the conversation will explore how men pursue idealized visions of masculinity through various means — from steroids to social media performance — and what these pursuits tell us about gender, desire, and embodiment in contemporary culture. If you've found this article thought-provoking, I encourage you to check out Yasha’s Substack and tune in for what promises to be a fascinating discussion that will elaborate on many of the ideas presented here!

Introduction

In 2003, J. Michael Bailey published The Man Who Would Be Queen, a work that aimed to popularize and extend sexologist Ray Blanchard’s typology of male-to-female transsexuals. Bailey’s argument — that male-to-female trans people fall into two broad categories, the feminine homosexual transsexual and the autogynephilic male whose desire to transition is rooted in sexual arousal at the idea of themselves as women — was as polemical as it was influential. In many ways, it served as a Rorschach test for the cultural understanding of gender identity at the dawn of the twenty-first century: welcomed by some as a refreshingly empirical look at gender variance, condemned by others as a reductionist and pathologizing affront to trans lives.

But for all the scrutiny that The Man Who Would Be Queen received, for all the moral panic it incited and the valuable debate it catalyzed, its most striking omission has rarely been addressed. If autogynephilia describes the erotic or psychological fixation on becoming female, then autoandrophilia would describe the attraction to oneself as an idealized male: an inwardly directed form of gendered desire focused on hypermasculine embodiment.

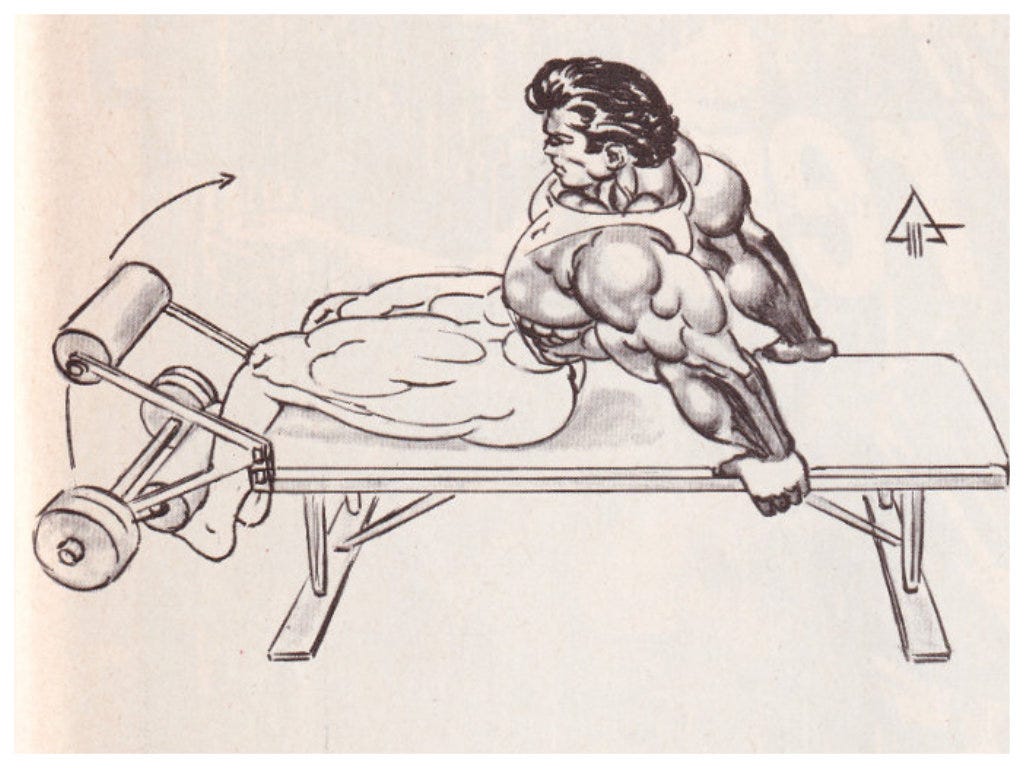

That dismissal was, and remains, a major oversight. Over the past decade, through my own long-form cultural journalism and interviews with powerlifters, steroid users, trans athletes, and gender nonconforming bodybuilders, I’ve encountered recurring narratives of self-directed masculine idealization. These individuals — often men, sometimes genderqueer or genderfluid, very occasionally female — were not simply performing masculinity in the sociological sense. They were constructing and pursuing an erotic or aspirational vision of themselves as heightened, perfected, larger-than-life male bodies. And they were doing so through rigorous bodily transformation: anabolic steroids, surgical enhancements, rigorous training, curated online presentation. It was gender transition, of a kind — one that remained within the male register but pushed it “to the moon.”2

This paper serves as a counterpoint to The Man Who Would Be Queen, engaging Bailey's arguments critically but charitably. I propose autoandrophilia as a cultural analytic — not a clinical diagnosis — to reframe how we think about masculinity, hormone use, and the erotics of self. Drawing from extensive reporting and interviews with individuals whose experiences challenge binary frameworks, I aim to illuminate what Bailey overlooked: that hypermasculine self-idealization operates through strikingly similar psychological mechanisms as the autogynephilia he documented so thoroughly.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Oliver Bateman Does the Work to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.