The Work of Chevron Deference

As of today, here's some work law students won't have to do anymore

For nearly 40 years, “Chevron deference” has been a cornerstone of American administrative law. The doctrine, established in 1984 in a decision by John Paul Stevens that has since been anthologized in countless administrative law casebooks, required courts to defer to federal agencies' reasonable interpretations of ambiguous statutes. But earlier today, the Supreme Court overturned Chevron in a 6-3 decision, fundamentally altering the balance of power between courts and agencies.

This seismic shift raises profound questions about so-called “expertise,” democratic accountability, and the nature of governance in a complex, polarized society. To understand its implications, we need to look beyond the legal arguments and examine the deeper tensions at play.

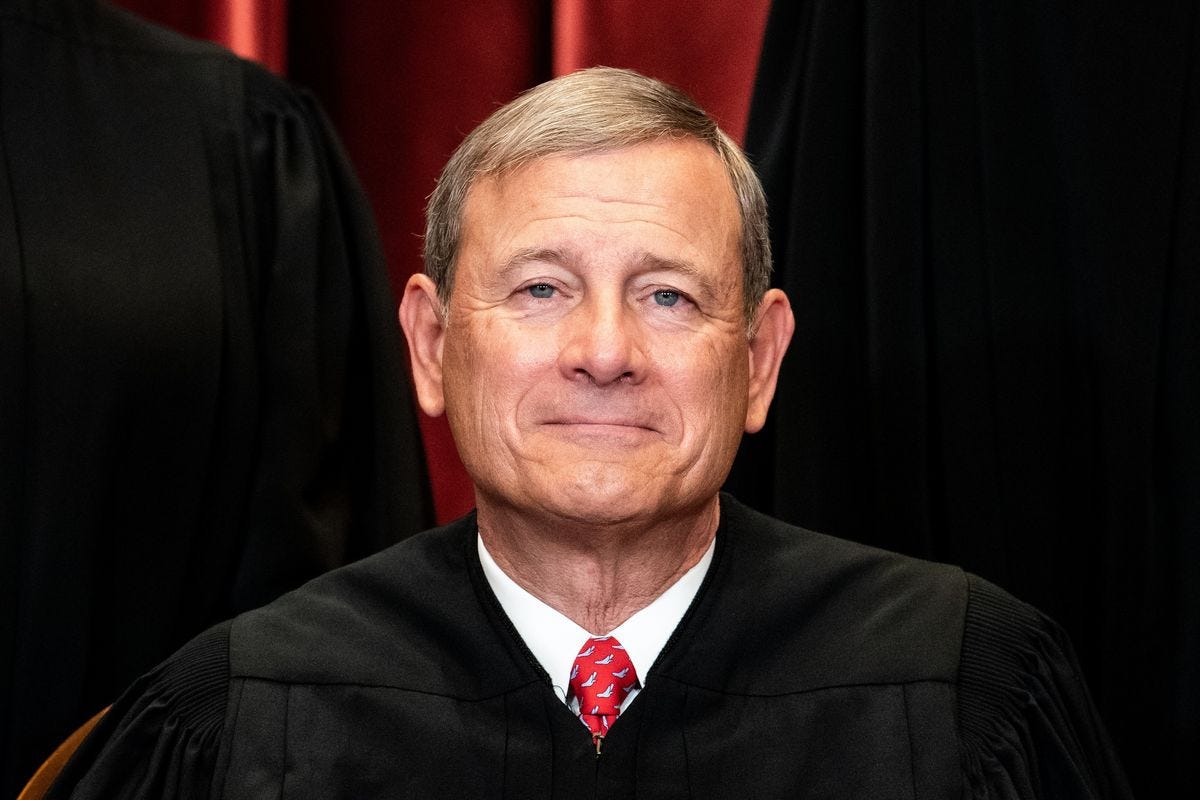

John Roberts Does the Work

The majority opinion, authored by Chief Justice John Roberts, held that Chevron was incompatible with the Administrative Procedure Act (APA) and the proper role of courts in interpreting statutes. The core of the majority's argument is that Chevron contradicts the text of the APA, which directs courts to “decide all relevant questions of law” when reviewing agency actions.

Roberts writes:

Chevron defies the command of the APA that 'the reviewing court'—not the agency whose action it reviews—is to 'decide all relevant questions of law' and 'interpret . . . statutory provisions.' §706 (emphasis added). It requires a court to ignore, not follow, 'the reading the court would have reached' had it exercised its independent judgment as required by the APA.

The majority also argues that agencies lack special competence in resolving statutory ambiguities compared to courts. While agencies may have technical expertise, the majority contends that statutory interpretation is squarely within the judicial wheelhouse.

Additionally, the majority claims Chevron rests on a fiction — the idea that statutory ambiguities represent an implicit delegation of interpretive authority from Congress to agencies. Roberts argues there's no basis to assume Congress intends such delegation.

Finally, the majority opinion emphasizes Chevron's alleged unworkability, pointing to inconsistent application by lower courts and the proliferation of exceptions and limitations over time. The majority portrays Chevron as a failed experiment that has only made administrative law more complex and unpredictable.

Elena Kagan Is Here for It

Justice Elena Kagan's dissent offers a spirited defense of Chevron and a not-half-bad critique of the majority's reasoning.

On the APA argument, Kagan contends that deferring to reasonable agency interpretations is fully compatible with a court “deciding” questions of law. She notes that courts still independently determine whether a statute is ambiguous and whether the agency's reading is reasonable.

Kagan forcefully disputes the claim that agencies lack relevant expertise:

The idea that courts have 'special competence' in deciding such questions whereas agencies have 'no[ne]' is, if I may say, malarkey.1 Answering those questions right does not mainly demand the interpretive skills courts possess. Instead, it demands one or more of: subject-matter expertise, long engagement with a regulatory scheme, and policy choice.

On Congressional intent, the dissent argues Chevron reflects a sensible presumption about what Congress would want when statutes contain ambiguities. Given agencies’ expertise and accountability, Kagan contends Congress would generally prefer agencies rather than courts to resolve such ambiguities.2

Perhaps most pointedly, the dissent accuses the majority of violating principles of stare decisis — the doctrine of respecting precedent. Kagan emphasizes Chevron’s deep entrenchment in administrative law and argues overturning it will massively disrupt settled expectations across the government and economy.

The Illusion of Expertise

One of Chevron's main justifications was that agencies have specialized expertise. Recent events, however, have forced us to question what “expertise”3 really means in practice.

The COVID-19 pandemic provides one such example. Agencies like the CDC issued guidance on measures like 6-foot distancing and masking that seemed to change frequently, often with minimal evidence beyond what we now know amounted to little more than feels and vibes. These decisions reshaped daily life for millions, yet at times appeared to be made on a whim.

This isn’t to say agencies never have valuable expertise. But it’s a reminder that “expert” decision-making can be influenced by politics, groupthink, and simple human error just like any other kind of decision-making.

The question, then, isn't simply whether agencies or courts have more expertise. It’s about how we evaluate and apply expertise in a democratic society. When does technical knowledge trump other considerations? How do we balance expertise with other values like transparency and accountability?

Unelected Officials and Democratic Accountability

Both federal agencies and federal courts exist partly outside the reach of democratic majorities. They’re staffed by unelected officials who often serve for decades. So when we debate Chevron, we’re really debating which set of unelected officials we trust more.

Federal judges, while unelected, do go through a public confirmation process. Their decisions are generally public and must be justified in written opinions. There’s a degree of transparency and accountability there, even if it’s far from perfect.

Agency decision-making, in contrast, often happens behind closed doors. Career bureaucrats who never face public scrutiny can shape major policies. There’s value in their expertise, but also risks of capture by special interests or detachment from democratic will.

So while neither courts nor agencies are directly accountable to voters, courts at least operate with a bit more sunlight. This doesn’t necessarily make them better decision-makers, but it does change the nature of their power.

The Red-Blue Power Shift

Overturning Chevron doesn't just move power from agencies to courts in the abstract. In practice, it likely shifts power from blue states to red states, even if indirectly.

Federal agencies, especially under Democratic administrations, have often pushed progressive policies that couldn't get through Congress. Republican-appointed judges have frequently been the ones trying to rein in what has been variously called the “administrative state,” the “deep state,” and (at least by me and my late father) the “diape(r) state.”

By giving courts more power to interpret statutes, the Supreme Court has created more opportunities for conservative judges to block liberal agency actions. It’s not a direct transfer of power to red states, but it tilts the playing field in their favor.

This isn’t necessarily good or bad — it depends on your political perspective. But it's a valuable subtext to the whole Chevron debate that sometimes goes unmentioned.

Implications and Ripple Effects

No matter how you slice it, the fall of Chevron will have far-reaching consequences:

Increased judicial power: Federal judges will now have the final say on many more questions of statutory interpretation. This shifts significant power from agencies to courts.

Regulatory uncertainty: Many longstanding agency interpretations may now be vulnerable to fresh legal challenges. This could create instability across numerous regulatory domains.

Slower rulemaking: Agencies may become more cautious in interpreting statutes, fearing stricter judicial review. This could slow the regulatory process. “Overproduced elites” who can’t find a job (i.e., not elites at all) should probably stop hoping for anything resembling federal student loan debt relief, despite Biden’s various confused efforts on that front.

More technical/scientific questions in court: Judges will be forced to grapple with complex technical and scientific issues previously left largely to agency expertise.

Heightened political polarization of administrative law: Without Chevron as a mediating doctrine, judicial ideology may play a larger role in regulatory cases.

Beyond administrative law, this decision may signal broader shifts in the Court’s jurisprudence. It suggests a willingness to overturn major precedents and a skepticism toward agency power. This could foreshadow further changes in areas like executive authority and the regulatory state.

The decision also exemplifies the current conservative majority’s muscular approach to shaping the law. Rather than incremental change, the Court seems increasingly willing to issue sweeping rulings that dramatically alter the legal landscape.

Deeper Questions for the Deep State

Ultimately, the fall of Chevron forces us to grapple with some fundamental tensions in our system:

How do we balance expertise with democratic accountability? We want people who understand complex issues making decisions, but we also want those decisions to reflect the will of voters.

In an age of polarization, is there any truly neutral arbiter? Both agencies and courts can be influenced by ideology. Is there a way to interpret laws that isn’t inherently political?4

How much stability do we need in governance? Chevron provided a degree of consistency in regulatory interpretation. Without it, will policy swing more dramatically with each change in administration or court composition?5

Who do we trust to make decisions when Congress hasn’t been clear? Agencies may have subject-matter expertise, but courts have experience in textual interpretation. Which skill set do we value more?6

How do we ensure that "expertise" is genuine and applied in the public interest, rather than being a shield for bureaucratic or ideological agendas?7

These questions don’t have easy answers, but they’re crucial to understanding the real stakes of the Chevron debate.

The Way Forward

The demise of Chevron doesn't solve these challenges; it simply changes the battlefield on which they'll be fought. Moving forward, we should consider:

More robust public debate about agency decision-making. If courts will be scrutinizing agency interpretations more closely, agencies need to be more transparent about their reasoning.

Congress may need to legislate with more specificity. If they want agencies to have interpretive power, they'll need to delegate it more explicitly.

Reforms to make both the judiciary and agencies more accountable without compromising their independence.8

Voters paying more attention9 to lower court appointments, not just Supreme Court picks. These judges will now have much more influence over regulatory policy.

Developing better mechanisms for incorporating genuine expertise into decision-making while maintaining democratic accountability.

Rethinking how we train judges, given their expanded role in technical and scientific matters.

The fall of Chevron deference is about much more than administrative law. It’s about power, expertise, democracy, and the fundamental challenge of governing a complex society.

By shifting power from agencies to courts, the Supreme Court hasn't solved these challenges. It has simply changed who gets the final say in answering them. In the short term, this likely means more conservative influence over regulation. But in the long term, it means we all need to think harder about who we trust to make decisions and why.

The experts haven’t gone away. The hard questions haven’t disappeared. We’ve just changed the rules of the game. Whether that's an improvement remains to be seen. But one thing is certain: the debate over how to balance expertise, democratic will, and the rule of law is far from over. If anything, it’s just beginning.

As we navigate this new landscape, we’ll need to remain vigilant. We must ensure that in our quest to rein in unaccountable bureaucrats, we don't simply empower unaccountable judges. We must find ways to acknowledge expertise without blindly deferring to it. And we must strive to create a system that can adapt to complex challenges while remaining true to democratic principles.

The death of Chevron marks the end of an era in American administrative law. But it also marks the beginning of a new one — one where we’ll have to grapple more directly with the tensions inherent in modern governance. It’s a daunting task, but also an opportunity to build a system that better serves the needs of a large and rapidly changing society.

In the end, the fall of Chevron serves as a reminder that even seemingly settled law can change dramatically. As the late Justice William Brennan was fond of remarking, in a world of nine justices, all it takes is five votes to rewrite the rules. That’s a sobering thought for anyone who cares about legal stability and the rule of law. But it’s also a call to engagement — a reminder that the shape of our governance is not fixed, but continually evolving. It’s up to all of us to help guide that evolution in a direction that serves the common good. We’ve got to do what we must, because we can.

Of course they would. A lot of modern statutes are massive and messy, and courts are pretty much only qualified to slap legislatures on the wrists for bad drafting — the now-overturned Roe v. Wade, for all its other merits and demerits, was a leading example of bad judicial draftsmanship in the course of attempting to legislate from the bench. Blackmun, a well-meaning, fog-brained homunculus who kept track of every meal he ever ate and every book he ever read, was one of the sloppiest writers and legal analysts in the Court’s recent history. The most egregious example of his kitchen-sink approach to writing was Flood v. Kuhn, an opinion that a) comes to a deeply unsatisfying and even rather stupid conclusion about baseball’s sacrosanct (and wholly undeserved) anti-trust exemption and b) appears to exist primarily so that Blackmun could list the names of his favorite baseball players: “Then there are the many names, celebrated for one reason or another, that have sparked the diamond and its environs and that have provided tinder for recaptured thrills, for reminiscence and comparisons, and for conversation and anticipation in-season and off-season: Ty Cobb, Babe Ruth, Tris Speaker, Walter Johnson, Henry Chadwick, Eddie Collins, Lou Gehrig, Grover Cleveland Alexander, Rogers Hornsby, Harry Hooper, Goose Goslin, Jackie Robinson, Honus Wagner, Joe McCarthy, John McGraw, Deacon Phillippe, Rube Marquard, Christy Mathewson, Tommy Leach, Big Ed Delahanty, Davy Jones, Germany Schaefer, King Kelly, Big Dan Brouthers, Wahoo Sam Crawford, Wee Willie Keeler, Big Ed Walsh, Jimmy Austin, Fred Snodgrass, Satchel Paige, Hugh Jennings, Fred Merkle, Iron Man McGinnity, Three-Finger Brown, Harry and Stan Coveleski, Connie Mack, Al Bridwell, Red Ruffing, Amos Rusie, Cy Young, Smokey Joe Wood, Chief Meyers, Chief Bender, Bill Klem, Hans Lobert, Johnny Evers, Joe Tinker, Roy Campanela, Miller Huggins, Rube Bressler, Dazzy Vance, Edd Roush, Bill Wambsganess, Clark Griffith, Branch Rickey, Frank Chance, Cap Anson, Nap Lajoie, Sad Sam Jones, Bob O'Farrell, Lefty O'Doul, Bobby Veach, Willie Kamm, Heinie Groh, Lloyd and Paul Waner, Stuffy McInnis, Charles Comiske, Roger Bresnahan, Bill Dickey, Zack Wheat, George Sisler, Charlie Gehringer, Eppa Rixey, Harry Heilmann, Fred Clarke, Dizzy Dean, Hank Greenberg, Pie Traynor, Rube Waddell, Bill Terry, Carl Hubbell, Old Hoss Radbourne, Moe Berg, Rabbit Maranville, Jimmie Foxx, Lefty Grove. [Footnote 3] The list seems endless. And one recalls the appropriate reference to the "World Serious," attributed to Ring Lardner, Sr.; Ernest L. Thayer's "Casey at the Bat"; [Footnote 4] the ring of "Tinker to Evers to Chance"; [Footnote 5] and all the other happenings, habits, and superstitions about and around baseball that made it the "national pastime" or, depending upon the point of view, "the great American tragedy."” Yes, this silly prose really exists in black and white in the U.S. Reports!

In his provocatively titled book The Death of Expertise (click there to read it), Georgetown PhD and long-time public intellectual Tom Nichols serves up a spicy takedown of what he sees as America's growing disdain for established knowledge. While I wasn't sold on his argument, some of you might be. Nichols claims we're witnessing not just healthy skepticism, but a full-blown rejection of expertise in favor of a "my ignorance is just as good as your knowledge" mentality. He paints this trend as a potential death knell for informed democracy — a bit dramatic, perhaps, but the man is good at driving engagement, if nothing else.

Nichols points his finger at various culprits: the internet's information buffet, our tendency to mistake Google searches for genuine understanding, and a culture that seems to value feeling smart over actually being smart. He argues that while experts aren't infallible (shocking, I know), they're still more likely to get things right in their fields than your average Joe armed with a Wikipedia article (sure, why not). The book takes us on a tour of how this expertise-shunning plays out across different areas, from vaccine debates to political discourse.

What I found most interesting, even if I didn't fully buy into the doom and gloom, was Nichols' exploration of what actually constitutes expertise. It's not just about degrees, he argues, but also experience, peer recognition, and a willingness to keep learning and admit when you're wrong (imagine that in today's Twitter debates). He warns that if we continue down this path of expertise-denial, we might end up with a society that can't solve its big problems (probably) and falls prey to snake oil salesmen in suits (I mean, that’s pretty much the American Dream and our proud 248-year tradition; read Jackson Lears for more on that). While you might not agree with everything Nichols writes, his book certainly provides food for thought in our age of slacktivist hot takes and fly-by-night Substack experts.

Probably not.

Of course. It’ll be lots of fun for the hot-take and extremely-online outrage classes in both parties.

I know where I’m laying the heavy jack…

You can’t. It’s all frens/enemas now, kiddos.

I think we should elect them all, but nobody agrees with me. You can read that “take” here: “As Melinda Gann Hall and Chris Bonneau argue in their book In Defense of Judicial Elections, elites trumpeting the merits of judicial independence are essentially “waging war on the democratic process.” The Supreme Court offers a particularly glaring example of these undemocratic forces at work. Only four of the current justices were appointed during the past two presidential administrations, meaning millions of voters in their late twenties and early thirties have had no say in the selection of a majority of the court’s personnel. Granted such tremendous job security, the justices are not only protected from the more sordid realities of politics but sometimes completely out of touch with reality. Former justice David Souter, who retired in 2009, joined the court in 1990 never having owned a television set and unaware of the existence of Diet Coke or the music of Motown. More troublingly, recent appointee Elena Kagan, the court’s youngest member at 54, has admitted “the justices are not necessarily the most technologically sophisticated people” and that social media remains “a challenge for us”—a highly problematic statement given the complicated cases about wiretapping, surveillance, and digital communications that the Supreme Court must decide.”

They won’t. There’s too much “timepassing” work with the Post Hand (PH) and Goon Hand (GH) left to do to waste prime edging hours on that geek/nerd stuff.

Hearing the automated voice say “Elena Kagan is here for it” made me laugh out loud at the gym