I recently spoke with artist Alex Graham about her new book The Devil's Grin Volume One from Fantagraphics. Graham's pandemic-era Dog Biscuits established her reputation as a no-holds-barred chronicler of the human experience.

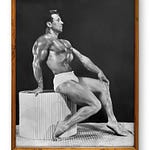

Portrait of the Cartoonist

Graham's journey to comics wasn't straightforward. She originally aspired to be a novelist, completing a 300-page novel at 21 with the naive expectation1 that "the success that follows finishing a novel was imminent." When that didn't materialize — she printed ten copies and doesn't think anyone read it — she realized difficulty of getting people to engage with "just words on a page."

Terry Zwigoff's Crumb documentary changed her direction. Her father showed it to her, and like many cartoonists, it transformed her understanding of what comics could do. But the technical side stumped her for years. The long-time painter thought comic layouts required "a mathematical formula" until fellow underground cartoonist Noah Van Sciver showed her the truth: "You just draw squares on the page and you fill them in."

A Refusal to Condescend

Graham won't tell you who's good or bad in her stories. Characters exist in all their messy humanity, with motivations tangled and unresolved. "I don't like work that talks down to me and tells me what I'm supposed to think," she said. "I want to go on the path all by myself over on the side that nobody else is walking."

Her visual style matches this philosophy. She creates rough, raw pages inspired by Weirdo magazine's grittiest contributors. Critics who complain about her drawing get compared to people "complaining about the way Bob Dylan sings….it's not conventional, it's different."

The characters’ expressive eyes haunt every panel. "Eyes are the window to the soul," Graham explained. "I want to reveal their inner monologue... even when no words are available."

The 1970s Without Modern Moralizing

Most of The Devil's Grin takes place in the 1970s, and Graham committed to historical fidelity. "I'm not going to retroactively take the things we believe today and apply them back then," she stated. This means showing the era's sexual dynamics and social attitudes as they were, not sanitized for contemporary comfort.

Two sources sparked her interest in writing the book: Netflix's Night Stalker documentary about Richard Ramirez and Scorsese's The Last Temptation of Christ. The serial killer doc provided a blueprint for the demonic antagonist; the Scorsese film offered psychedelic spirituality. "I was just blown away," she said of the latter.

Making Rent With Substack and Patreon

Graham built her audience over 20 years, starting with painting. During COVID, cartoonist Simon Hanselmann shared Dog Biscuits, which caused her Instagram to grow from 3,000 to 20,000 followers. Now she posts daily Devil's Grin pages on Substack and Patreon.

"[Those two platforms] pay my rent every month," she said. This subscription income lets her spend a full day on each page. It’s a slower pace than Dog Biscuits' 3-4 pages daily but necessary for the detail work.

Other High Points

Art Isn't Therapy

"We’ve gotten so confused about how to measure the quality of art in the last 10 years that nobody understands what [quality] means anymore," Graham observed. "A lot of people seem to think that art is for teaching us how to be better people and for showing that you’re a good person. But that's the worst art."

Live First, Draw Later

"Get out and live your life when you're in your twenties," Graham advises young cartoonists. "If you sit at a desk for your entire twenties, you're just gonna start regurgitating until every comic you make is just about you drawing comics. Live the stories that you'll be telling for the rest of your life."

The Demand for Non-Didactic Work

Graham sees opportunity in the current landscape: "So many people are neglecting to actually try to entertain. First and foremost, I feel like I’ve been able to gather and then hold an audience by entertaining them."

During the pandemic, people shared Dog Biscuits because it gave them what they were likely struggling to find elsewhere: messy relationships, uncomfortable truths, characters who felt real rather than representative. "My stories are kind of like a soap opera," she said.

Handmade Art

Graham's friend Michael Kupperman has predicted that handmade art will surge in value as AI slop proliferates: "When something is made by hand, you can feel the spirit of the person in it."

Her process embodies this: printer paper, micron pens, sharpies. You can see the human decision in every wonky eye, every rough edge. As AI perfects the slick and formulaic, these imperfections become the proof of consciousness.

What Graham Doesn't Do

Graham doesn't distinguish heroes from villains. She doesn't resolve conflicts neatly. She doesn't update historical attitudes for modern sensibilities. In our current moment, such omissions feel radical.

We also discussed Pee-wee's Playhouse2 and Paul Reubens' approach to diversity as he described it on the can’t-miss Max documentary mini-series: "The way I did inclusion was by never talking about it." In her work, diverse casts and overlapping identities exist without announcement or explanation.

AI and the Future

"Maybe AI will help us remember what we actually value," Graham suggested. If machines can successfully replicate paint-by-numbers Marvel movies and thumbsucking "prestige" TV series, perhaps that highlights what only humans can make: the weird, uncomfortable, specific, and strange.

The first volume of The Devil's Grin exemplifies that irreplaceable human weirdness. Volume 2 will take another 3-4 years to finish. That’s painful for completists like me, but such is life.

Graham's work reminds us what art can accomplish when it trusts its audience.

Follow her progress on Substack or Patreon, buy her paintings, or read Dog Biscuits for pandemic-era soap opera with bite.

The artwork for Oliver Bateman Does the Work (and the What’s Left? podcast before it) was created by the incomparable Danny Hellman.

Totally understandable, though. We’ve all been there. During our conversation, I shared my own moment of artistic clarity from years ago. After reading Hubert Selby Jr.'s splendid Last Exit to Brooklyn, I had the typical young writer's response: "I only want to write books that are like Last Exit to Brooklyn." Fight that impulse immediately! You’re not from Brooklyn. You’re not from the streets. You can't write someone else's experience. You have to write from your own life, your own observations, your own weirdness.

Another digression: my dad, who introduced me to William Burroughs’ Naked Lunch and wrote like a much nuttier Selby (though certainly not by design), also grew to love Selby’s work. Not everyone does; some see him as a closet moralizer, and I suppose that’s okay by me because I am too.

Read that hyperlinked article: “Reubens curated a remarkable ensemble of performers, including Phil Hartman, John Paragon, Lynne Marie Stewart, Laurence Fishburne, and S. Epatha Merkerson, among others. The creative vision of the show was a collaborative effort by various accomplished artists and musicians, including Panter, Wayne White (a painter and puppeteer who voiced several characters), Danny Elfman (of Oingo Boingo and Tim Burton film-scoring fame), Mark Mothersbaugh (Devo), The Residents, and others. Gary Panter recalled the chaotic first day of production, “Where’s the plans? All the carpenters are standing here ready to build everything,” the set workers asked. Panter had responded, “You just have to give us 15 minutes to design this thing!” They did, and the pace never decreased. “I was writing an album’s worth of music once a week, and it was really exciting,” added Mothersbaugh.”

Share this post