The Work of Socialism in One Country

Ber Borochov's theory of localized self-determination and class solidarity could address dilemmas that have baffled the Left

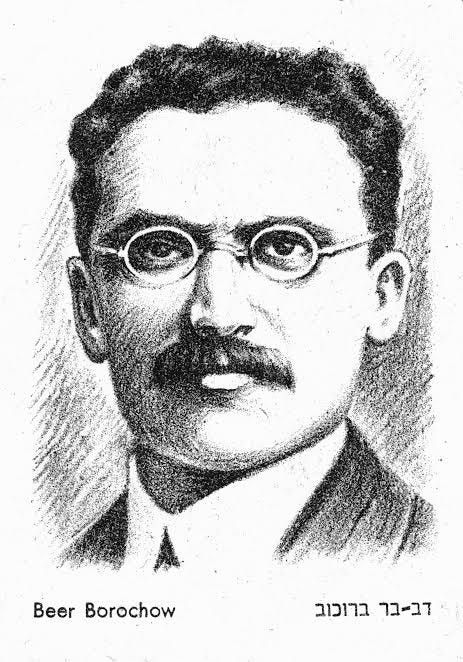

Ber Borochov (1881–1917) was a leading thinker among fin-de-siècle socialist Zionists. He made his bones by arguing that Jews — like all supposedly “stateless”1 peoples — needed the means to produce, develop class organizations, and control a homeland so their economic and social lives could flourish without perpetual displacement.2 He applied a Marxist lens to issues that standard Marxism had theretofore mostly3 brushed aside: how territory, culture, and economics weave together to shape national conflicts. Born in Ukraine, he grew up watching how local fights for farmland and factories dovetailed with imperial power struggles. By the early twentieth century, he was immersed in writing and research about capitalism, migrations, and the emergent sense of national self. In 1905, he published The National Question and the Class Struggle, outlining how society splits into classes but also into distinct national groups, each shaped by “relatively distinct conditions of production.” This pamphlet foreshadowed conflicts that, more than a century later, still drive political flare-ups across continents.

When Angela Nagle wrote “The Left Case against Open Borders” for American Affairs Journal 2018, many left-leaning intellectuals reacted with outrage. Nagle had already gained attention for her book Kill All Normies, which dissected certain online subcultures, but that immigration essay crossed a line. In it, she argued that uncritical support for unlimited migration often helps corporations exploit cheap labor, undermines local wages, and strips poorer countries of skilled workers. Critics pounced on this fairly modest argument and called her a “class traitor” and a “reactionary.” By the standards of that now-bygone era, she was effectively “canceled,” or driven out of certain media circles that once praised her. Yet Ber Borochov’s arguments about how oppressed groups need local control — over farmland, industries, and resources — echoed through her piece.4 Both authors traced similar lines: capitalism’s global expansion can sever communities from their normal economic base and trigger mass migrations that feed the profits of those at the top.

Even a cursory reading of Borochov’s 1905 text shows why it resonates. He pointed out that people cannot survive without producing goods, and that “in order to produce, they must combine their efforts in a certain way.” The forces of production — machinery, farmland, labor, resources — are always organized within a definite territory. That territory can be small or vast, but the group that depends on it gradually sees itself as a distinct social entity. In some cases, that group’s identity coalesces into what we now call a “nation.” Societies then clash whenever one group tries to defend its conditions of production or expand them into someone else’s domain. Borochov did not excuse conquest or ethnic domination; he wanted to show that nationalism arises when real material concerns push people to rally around the idea that “we must own and manage our base of production.”

In his day, some Marxists dismissed such talk as “bourgeois nationalism” or petty distraction from the class struggle. But Borochov saw no contradiction in discussing both class and nation. He called them intertwined.5 According to him, attempts at building class solidarity could fail unless workers secured territorial conditions stable enough to let them organize. If farmland, factories, or entire local economies were routinely controlled by foreign powers — or opened to a perpetual inflow of desperate labor — then that battered local workforce could never unify effectively. This argument caused uproar among orthodox Marxists. Yet from our vantage point, it clarifies how people can feel a deep need to protect local production, even if that desire is often labeled pejoratively as “nativism.”

His theory fits modern controversies. In Europe, talk of “sovereignty” ballooned when the European Union imposed strict austerity on countries like Greece. In the United States, certain regions found themselves hollowed out by industrial outsourcing. Campaigns soon emerged that promised to “bring back jobs,”6 sometimes laced with anti-immigrant rhetoric. Elsewhere, smaller nations stripped of control over their resources faced internal strife. The intractable Israeli-Palestinian conflict, ironically, is entangled in the same type of question — who controls farmland, housing, and local industry.7 Borochov remains relevant because he recognized that national attachments are not an arbitrary myth. They often reflect a group’s direct relationship to the land or industries that support them.

Angela Nagle’s brief but fascinating main-character arc shows how these ideas can spark fury even on the contemporary Left. Her essay suggested that open-borders enthusiasm among well-off Westerners might serve powerful global interests more than it helps actual migrants. She singled out the role of corporate lobbying groups who promote high immigration to keep labor cheap and unorganized. That stance angered left-liberal pundits who believed any critique of large-scale immigration smacked of xenophobia. For a time, the uproar effectively sidelined her. Yet Nagle was echoing a logic that runs through Borochov’s century-old pamphlet: defending the well-being of a local working class — especially wages and job security — does not have to mean demonizing immigrants, but it does require confronting the profit-driven system that created these migrations in the first place. Borochov repeatedly stressed that migrations usually reflect harsh structural dislocations. People rarely uproot themselves unless they have few options for survival at home.

The notion that local self-determination is indispensable goes back centuries. Borochov updated it for the industrial age, insisting that a landless group, starved of control over local production, could not flourish. He argued this specifically for Jewish workers, but the principle extends to any marginalized population. His explanations fit how populations in the Global South lose farmland to corporate agribusiness, see their wages undercut by foreign imports, and then depart in search of menial work in the wealthiest countries. If those countries present open borders, that might be good for certain migrants individually. Yet it may also free big corporations to exploit vulnerable labor at will, while crippling union efforts and draining human capital from the poorer nation. Neither Borochov nor Nagle wanted to punish migrants. Both raised the alarm about underlying conditions that push people to migrate in the first place — and about who profits most from the chaos.

What often gets left out of the debate is how territory fosters or wrecks class movements. “Production,” Borochov wrote, “cannot be separated from the land in which it takes place.” He asked readers to consider how feudal restrictions once carved territory into tiny fiefdoms. Only with the bourgeois revolutions did populations unify these territories into nation-states that allowed capital to flourish under one set of laws, languages, and trade systems. Eventually, though, capitalism turned that national framework into a platform for expansions and conquests. States that seemed stable discovered that the global push for cheaper labor or raw materials forced them into collisions with rival powers — and into domestic friction over whether free trade or open borders truly benefited the mass of workers.

We see this friction on a grand scale now. Corporations push for uniform labor and environmental standards to facilitate global supply chains and borderless financial flows. At the same time, wages are deliberately kept low or lowered via various methods both fair and foul. Agricultural giants can outcompete local farmers in developing regions, prompting mass exodus. Then the giant tech or service industries in the developed world can hire the cream of the workforce in that artificially-depressed region at low wages. Meanwhile, the losing region suffers “brain drain” and an accompanying reduction in tax revenue. That cycle might seem unstoppable. Borochov’s text, though, reminds us that it is a function of how the “conditions of production” were forcibly reshaped across these regions. If the local workforce had real power to manage farmland or to enact strong labor laws, if the state were not systematically blocked from protecting its own industries, then fewer people would be driven away from home.

Borochov thus indicates that “national oppression” can coincide with capitalist exploitation in ways that hamper class solidarity everywhere. People forced to migrate become scapegoats in their new homes. Native workers, battered by wage stagnation, lash out at the newcomers as a threat. Politicians feed on that anger. The resulting tension splits workers and distracts them from the real profiteers. This scenario mirrors the struggles Angela Nagle described, as well as the real-world examples resulting from global trade deals. Some of her critics often claimed she wanted to shut out desperate refugees, especially BIPOC refugees. But that is a caricature. She was asking whether universal “open borders” simply ensures a never-ending supply of underpaid labor, with minimal regulations or employer accountability. That theme is exactly what got her “canceled.” She was accused of peddling a right-wing narrative. Yet from Borochov’s standpoint, her logic sits squarely in one part of the socialist tradition.8

The question is how to combine national self-determination — meaning an economy that answers to its people — and international solidarity. Angela Nagle, at least in broad terms, echoed Borochov by saying that genuine internationalism must rectify the structural inequities that cause displacement. Ensuring a robust local economy, open to unionization and local wage standards, can be more humane than letting capital push entire communities into forced migration. Many leftists in the late 2010s relied heavily on universal moral appeals about “no borders,” which appear to have helped fuel the very system they claim to resist.

Borochov offered a framework for a different approach. He wrote that “the national struggle . . . is not waged for ‘spiritual’ things but for certain economic advantages in social life.” Cultural slogans about tradition or identity can be a front for deeper concerns, especially when a state or corporate interest deploys them cynically. Yet in places where people’s entire livelihoods hang on farmland or local industry, the desire for national protection is not mere chauvinism; it is a survival reflex. Angela Nagle triggered outrage because she reminded left-leaning readers that those local reflexes cannot be waived away with moral condemnation. They are responding to basic conditions of production — jobs, wages, farmland, factories.

Another side of Borochov’s argument is that the same capitalism that fosters mass migration also produces a backlash among larger powers. Politicians rally voters by demonizing “illegals” and promising harsh crackdowns or walls. Those leaders rarely challenge the core system of exploitation.9 They want the benefits of cheap labor (or foreign resources) without facing the social blowback. That is why certain governments can be simultaneously anti-immigrant in rhetoric but quietly tolerant of unscrupulous employers paying illegal wages. Nagle’s piece exposed that contradiction, calling it a “farce” that punishes immigrants while letting corporations off the hook. Borochov, in a sense, predicted that dynamic when he described how elites consciously keep the workforce divided. He said, “This antagonism is artificially kept alive . . . by all the means at the disposal of the ruling classes.”

He also drew a line between the nationalism of an oppressive class — land barons or imperial elites — and the nationalism of an oppressed group that simply wants the normal conditions for its production. The first kind of nationalism aims to dominate or annex, while the second wants the freedom to stand on its own flat, turf-toed feet. That is partly how Borochov reconciled nationalism with socialist ideals. He believed oppressed peoples have “common historic interests” that unify them across class boundaries, at least until they achieve sovereignty. After that, class conflict reasserts itself. In modern times, we see that in independence movements across Africa or Asia: once foreign rule ends, local class divisions sharpen. Yet the initial struggle to break external control is national in character. For Borochov, it was essential that socialists not sneer at that quest for local autonomy.

Though his main concern in 1905 was the uncertain position of Jewish workers in Europe (leading him to propose a national homeland for them), his reasoning translates more broadly. Migrations from Mexico to the United States, for example, reflect deep structural crises of agriculture and trade. NAFTA dismantled many small farms and depressed local wages. Big agribusiness in the United States — often aided by government subsidies — flooded Mexico with cheap produce. That shift forced thousands to cross the border looking for work, enabling American employers to pay them sub-union (at times even sub-human) wages. This cycle was precisely what Nagle flagged. She pointed out that praising open borders or tolerance does little for these migrant farmworkers if they remain precarious and easily exploited. Without local sovereignty or local reforms that strengthen labor power, the entire setup is rigged to maximize corporate profits at the expense of both sets of workers.

Borochov described such a system as a “contradiction” that cannot be explained away unless one looks at how territory, wages, and power converge. Angela Nagle incurred backlash because she actually looked at that bigger picture, rather than repeating then-fashionable moral lines. That bigger picture is close to Borochov’s message: to fix these ills, we cannot ignore local conditions and indeed must start with them (even dwarfs started small, to borrow the title of a cult Herzog film). We must challenge the structural causes of forced migration and demand fair labor standards in both sending and receiving countries. We must stop letting transnational capital shape everything to its advantage.

He also recognized that building a stable territorial foundation does not mean closing out the rest of the world or demonizing all outsiders. It means ensuring that each society controls its own production in a balanced way. Once that baseline is established, real international cooperation can emerge. For him, the ideal future would be a kind of global alliance of self-determining nations, not walled-off enclaves. Yet the step of attaining that self-determination is crucial. He wrote, “No one is bound to accept the . . . notion that the proletariat has no national interest. . . . The worker must have a place to work.” If local workers watch jobs vanish, they protest. If foreign workers flood in — driven by their own crises — they get scapegoated, and the cycle of resentment goes on.

Much of the push to “cancel” Angela Nagle — silly in retrospect, but of a piece with the “zeitgeist” — stemmed from a refusal to let that conversation happen. She cut against the easy moral vantage that lumps every border restriction into bigotry. Her critics, like Atossa Araxia Abrahamian10 in The Nation, retorted that any argument acknowledging labor competition or wage depression must be inherently racist. This is exactly what Borochov predicted: the interplay between class and nation is constantly “obscured” by simplistic moral messaging. Some adopt a pseudo-cosmopolitan approach that inadvertently or perhaps even deliberately aligns them with corporate interests. The result, in Nagle’s words, is “moral blackmail,” in which anyone raising these deeper questions is pilloried.

Yet the decades since Borochov wrote have only offered further confirmation for his view that territory, sovereignty, and labor shape real struggles. The “era of globalization” has not swept away national boundaries so much as it has placed them at the service of multinational capital. People across the political spectrum sense that something about these open flows of money and uneven flows of labor is fueling discontent. The Right’s answer is typically to hurl abuse at foreigners. The mainstream liberal approach is to speak banally of tolerance while ignoring corporate profiteering. Angela Nagle tried to nudge the conversation in another direction — one that Borochov, were he resurrected and asked to write hot takes on the matter, would likely recognize. He would probably say we must arrange production so that nobody is forced to migrate en masse, and no local labor force is left insecure due to a massive influx. That means an international system that respects each population’s right to a decent livelihood — and penalizes employers who undercut wages by exploiting undocumented or precarious labor.

The biggest challenge is turning these insights into action. Borochov himself championed an organized Jewish working class that would found cooperatives and unify around socialist ideals, such as were seen with the later-in-time kibbutzim. He died of pneumonia at age 38 in 1917, before seeing how his theories would influence labor movements or how the Zionist project would develop. But the principle at the core of his message remains: national and class politics cannot be pried apart. Where local labor is too weak to shape economic policy, foreign or domestic elites will call the shots. That leaves workers unprotected, fueling intergroup tensions. Where local labor can defend its territory and wages, a better kind of internationalism can slowly take shape — one based on cooperation, rather than desperate migration or exploitative workforce swaps.

Today, as Left-leaning voices grappling with Trump’s reelection are weighing whether to champion open borders or some other framework, Borochov’s approach remains instructive. It does not reduce everything to nationality or romantic illusions of homeland. Instead, it highlights how wages, resources, and control over them define our real “national question.” A Left orthodoxy that insists on moral purity here risks skipping over details about who gains from cheap labor or how cross-border markets are manipulated. Borochov would say that socialists should refuse to take such purity tests, demand clarity about who truly benefits, and stand for strong local production conditions that empower the workforce. As soon as a society can address these issues, outward hostility will ease, and genuine solidarity — rather than moralistic token gestures — will become possible.11

The reason Borochov speaks to our era is that he rejects shallow universalism and populist nationalism alike. His work affirms that workers everywhere need a stable ground for unity, which can only arise if each group manages its resources without external sabotage. That is the deeper thrust of Borochov’s teaching: the real material conditions matter more than flowery slogans. Borrowing from him, one might say Angela Nagle’s big misstep was to pose an inconvenient truth: if we will not fix the structural causes that destroy local economies, then championing “unlimited migration” solves little and may even entrench the same capitalist patterns we claim to oppose.

At a time when “national questions” keep disturbing complacent assumptions — and when condemnation falls quickly on any liberals hinting at nuance — Borochov’s refusal to separate class and nation functions as a timely reminder. Real conditions of production shape the migration chaos, and moral condemnation alone will not solve it. We need12 universal worker rights, robust local economies, accountability for exploitative employers, and trade reforms that prevent entire populations from being forced to roam the globe for survival. That is what he meant by a territory “harmonizing the conditions of production.” It is neither jingoistic nor isolationist. It is socialism with a firm grip on reality, the kind that recognizes local attachments and tries to make them the basis for genuine international solidarity.

These concerns run counter to the atmosphere that got Angela Nagle canceled. Many want an easy moral stance — either tear down the walls entirely or throw them up higher — without confronting the corporate system behind it all. Borochov’s pamphlet did not let people off so easily. He spelled out that big labor migrations do not “just happen.” They arise from systematically arranged economic forces. That means we cannot have a genuine fix without reshaping production itself, from farmland to factory, in a way that stops pitting local workers against incoming waves of equally vulnerable labor. If that conversation is taboo, then we stay locked in a cycle of moral shouting and cheap-labor exploitation.

By reintroducing Borochov’s perspective, we get a clearer path forward for the Left: neither romantic illusions about borderlessness nor reflexive hostility toward migrants, but organized efforts to ensure each population can secure fair wages, stand on its own land, and partner with others as equals. That is where class struggle meets national rights in a constructive way. The long-forgotten attacks on Angela Nagle, so influential on that micro-generation of Millennial “Post-Leftists” who eventually became Republicans, show how threatened most commentators become when that idea is raised. Yet the global challenges of the present give us every reason to revisit it — and so, in that sense, Ber Borochov remains a valuable guide for the perplexed.

What is the national state but an “imagined community?”

And they got one. It’s working out great, really great, as the current POTUS might put it.

Always “mostly.” Lots of fish in that marxists.org sea, after all.

Borochov, however, remains “out of cite,” perhaps understandably so given Israel’s 20th and 21st century track record.

Whatever that means (usually nothing!).

It appears they are settling on a solution for this one.

Admittedly, the national socialist tradition…

Much less build the wall or even achieve deportations (expensive by any measure in 2025) at a rate much greater than prior administrations, PR stunts and harsh rhetoric aside (though it bears noting in the interest of remaining “fair & balanced” that border crossings, as of February 2025, are down).

Try saying that five times fast!

If it ever becomes possible, alas…

What we need is not what we will get, of course. “For who makes you different from anyone else? What do you have that you did not receive? And if you did receive it, why do you boast as though you did not?”

Borochov was out to lunch: https://nonzionism.com/p/dov-ber-borochov

Interesting, but Eurocentric. No mention of slavery or is primitive accumulation of capitalism's 'rosy early dawn.' (Marx). Some would argue that the growth of slave capitalism fed the industrial revolution in Europe, at least as much as the enclosures and the transition from feudalism. No mention of Africa at all.