This is an article that originally appeared in the now-defunct Pacific Standard (originally Miller-McCune) magazine, a publication to which I contributed occasional pieces from 2016 until it folded in 2019. PS was a great place to publish primarily because the editor with whom I worked, Ted Scheinman, was skilled and conscientious (his book on Jane Austen fandom is quite good, too).1

Written way back in December 2016, this was my first longform effort to attack the “take” genre — in this case, the style of take (of which there were so many) that attempted to explain Donald Trump’s rise to power in the context of pro wrestling. Such pieces were bad for many reasons, but what I found most irritating was how little their authors knew about wrestling itself; their understanding of the subject was confined to vague recollections of the late-90s “Attitude Era” of WWE and perhaps some clips of Vince McMahon getting his head shaved after losing his feud with Donald Trump (even Tyson Smith, author of the excellent Fighting for Recognition, wrote one of these tedious takes, but I can forgive him this trespass since he at least had done the (field)work).

Drawing on my contacts in the worlds of wrestling and theater, I sought to upend this paradigm. I showed how the seemingly intertwined aspects of Trump and pro wrestling about which prior hot-take authors had opined were actually part of the much longer history of America’s greatest cultural contribution: sales and marketing, stretching from P.T. Barnum’s circus and Charles Finney’s “anxious bench” to the work of Bruce Barton and his ilk on Madison Avenue. The sport of pro wrestling, meanwhile, was a style of partially choreographed, partially improvised physical performance presented by a tight-knit community of athletes.

Some interesting things happened in the years since the publication of this article, which was, I believe, unfairly ignored in its time — no actual sports journalist was writing anything remotely like this — or merely classified as yet another “Trump take” by those who bothered to skim it. In the ensuing years, the Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame closed. Although accounts differ regarding the details of the closure, it appears that Johnny Mantell and his wife struggled to raise the revenue needed to sustain the operation they had relocated from Amsterdam, NY to Wichita Falls, TX (after I left the PWHF’s board of directors in 2016, the remaining board members accused Mantell of misusing the nonprofit’s funds, though some sort of accommodation was later reached). Attorney Grey Pierson, who is also quoted in here, played some role in preserving parts of the collection before it could be claimed or reclaimed by historians previously associated with the NY incarnation of the PWHF. Pierson and Mantell provided invaluable assistance with my World Class Championship Wrestling photo exhibit at the University of Texas at Arlington, and I have nothing but positive things to say about these two men.

A successor hall of fame, the International Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame, opened last year in Albany, NY, and I’ve contributed biographical essays to their first two induction programs.

The text of the article below was revised for republication here on Substack, and now constitutes a more or less final version much closer to my original vision.2

Even people who have spent a lifetime ignoring professional wrestling are discovering they can overlook it no longer. President-elect Donald Trump has shaved heads and thrown clotheslines in the wrestling ring, incoming Small Business Administration Director Linda McMahon is a majority shareholder of the WWE, and a bevy of bruising cultural commentators get paid to conduct themselves more like opponents preparing for matches than colleagues debating the niceties of public policy.

If the language and postures of wrestling are increasingly apparent among the nation’s highest ranks, perhaps it’s time to consider seriously how the sport works. Such an assessment must go beyond the obvious points: Of course the results are predetermined, of course the personalities are loud and brash, of course the level of discourse is low and vulgar. These characteristics, coupled with a disregard for truth and reality and a selective amnesia regarding conflicts that occurred mere hours ago, are not necessarily unique to pro wrestling; they are shared broadly across a culture devoted to spectacles of all kinds. What, then, is special about pro wrestling? What has mainstream American culture actually borrowed from it, and what might it still have to learn?

When I need answers about pro wrestling, I go to the source: the Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame in Wichita Falls, Texas. The walls of that facility — located in a blue skyscraper sandwiched between the remnants of the city’s wind-swept, art deco downtown — tell a colorful and violent story about the popular culture of the past 150 years. Here, amid all the memorabilia — the sequined robes and embossed title belts — Johnny Mantell, a veteran of the ring wars, guides visitors while telling stories about the sport’s colorful past.

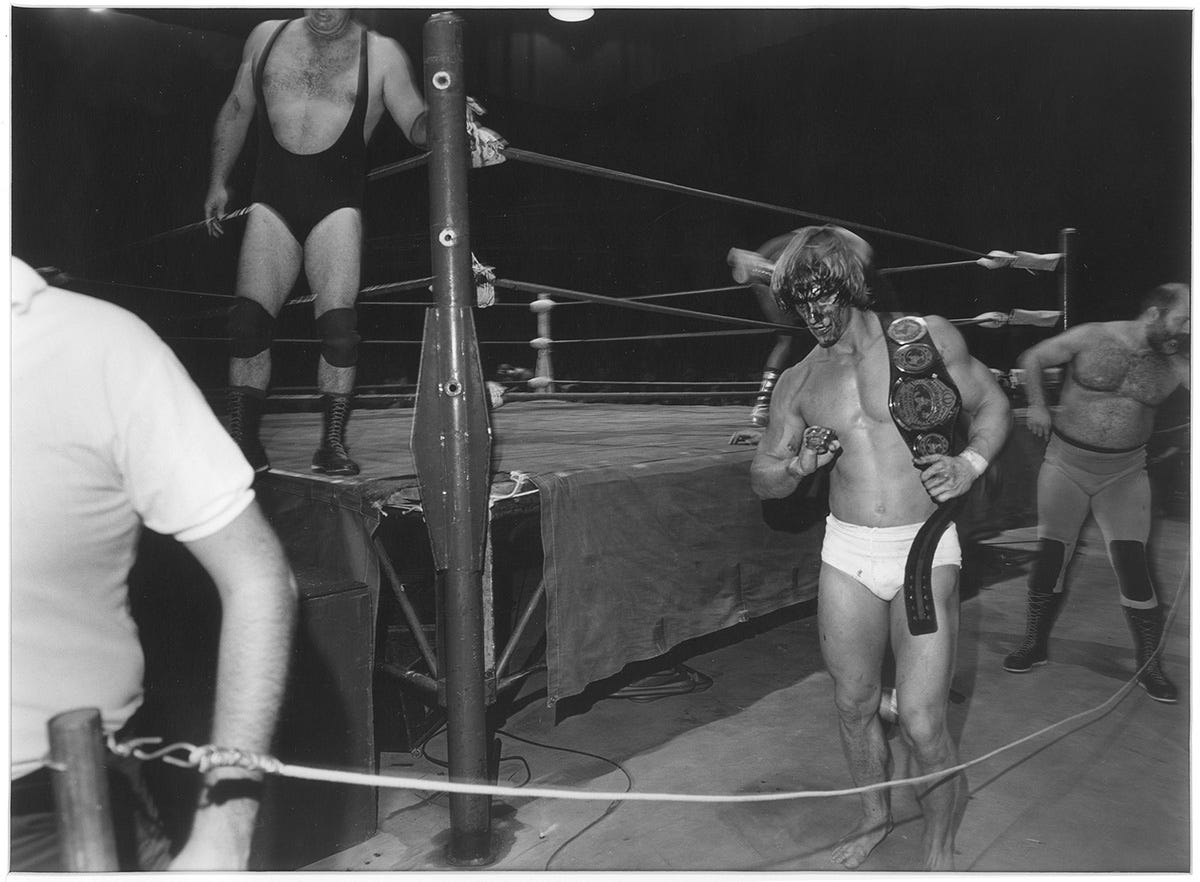

If one looks past the slightly slower gait and receding hairline, retired wrestler “Cowboy” Mantell still resembles the same 230-pound babyface who, during the early 1980s, participated in epic matches alongside the beloved Von Erich brothers and against hated rulebreakers “Gorgeous” Jimmy Garvin and Michael “P.S.” Hayes. Trained in Los Angeles by the late “Rowdy” Roddy Piper, Mantell was a capable performer whose talents have been praised by the likes of ex-WWE champions “Stone Cold” Steve Austin and John Bradshaw Layfield.

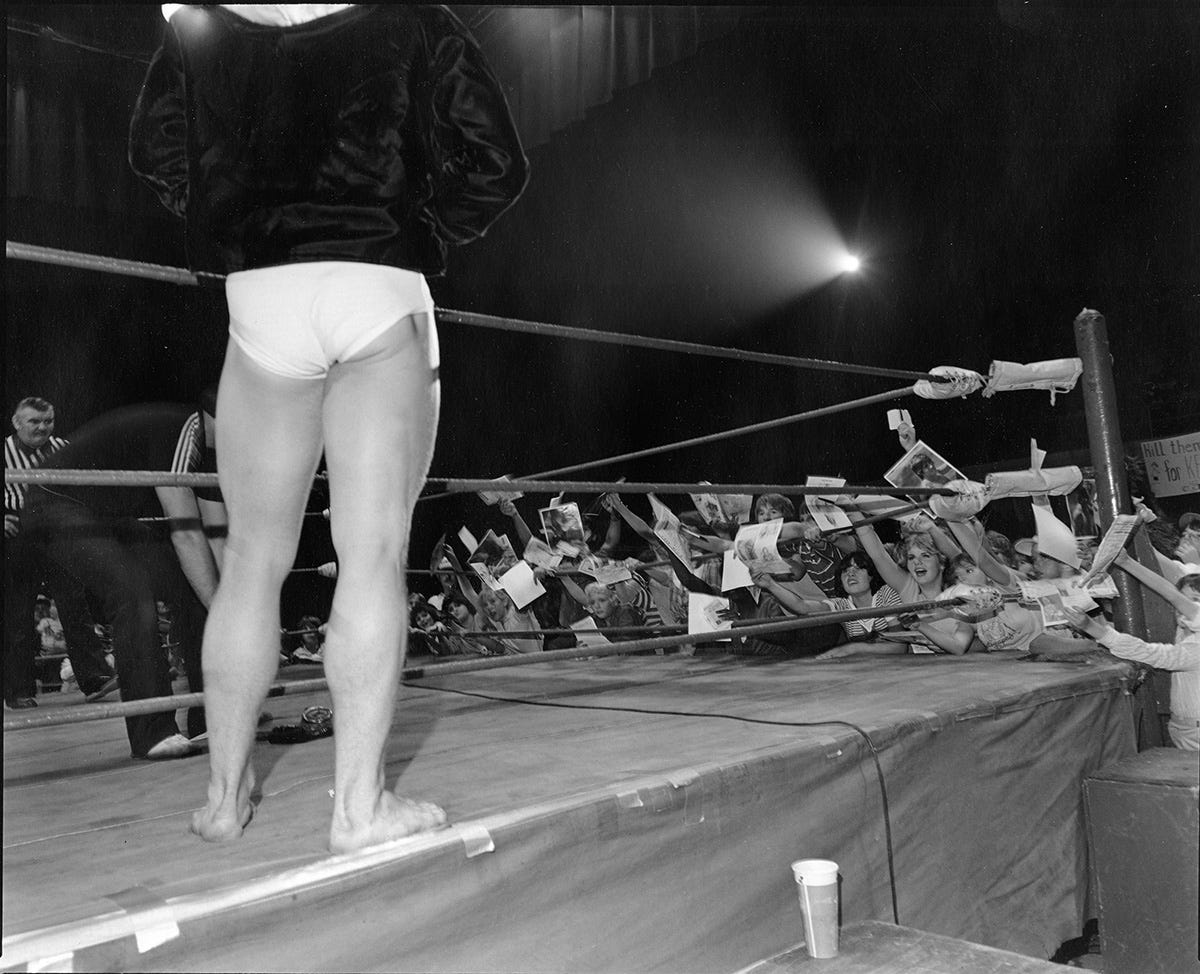

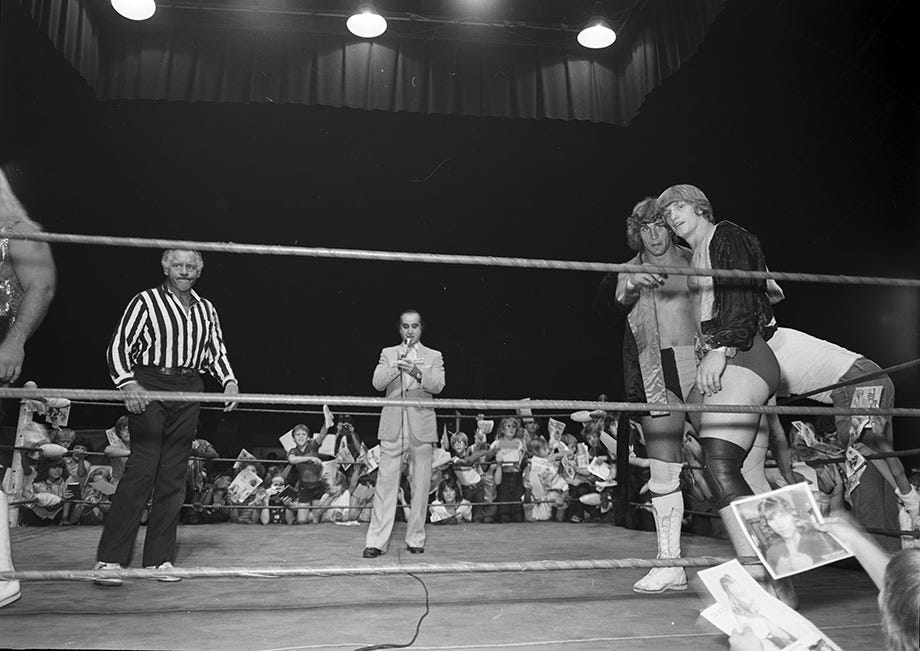

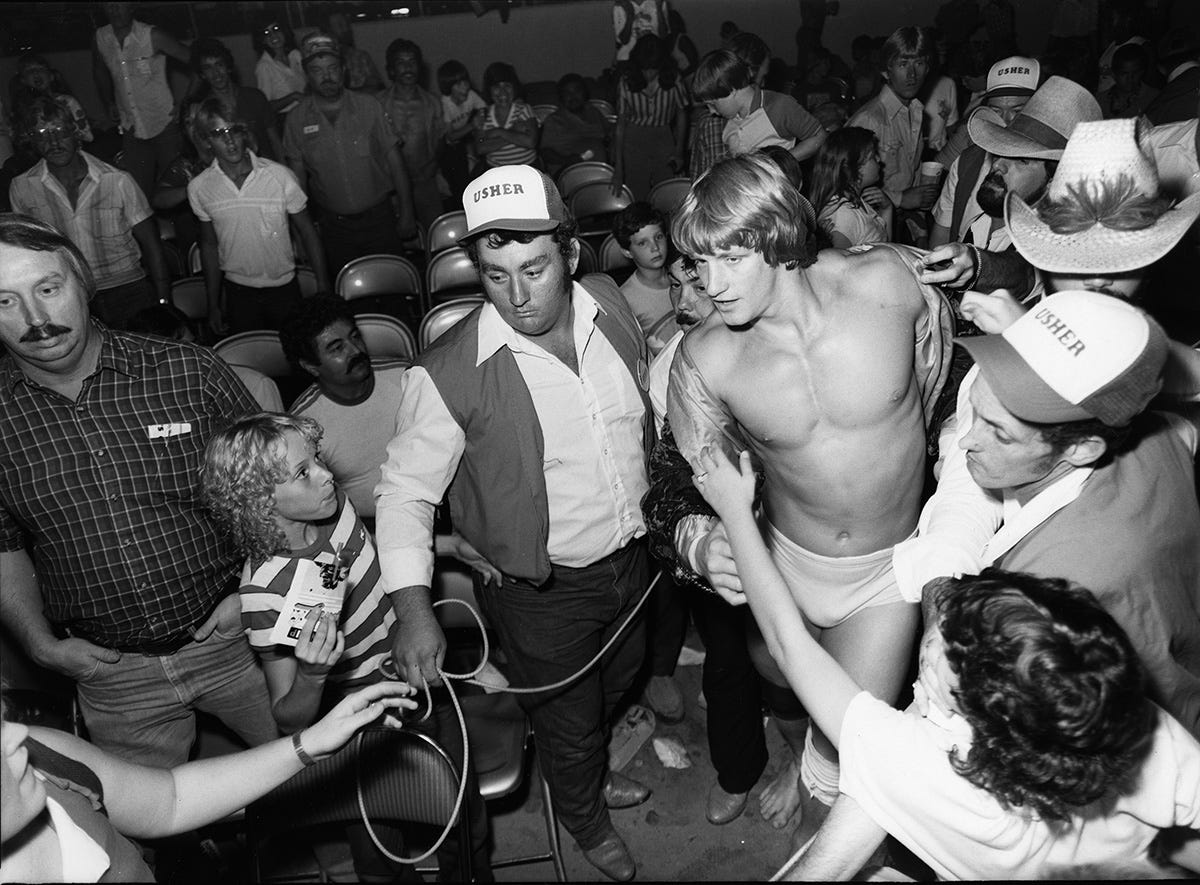

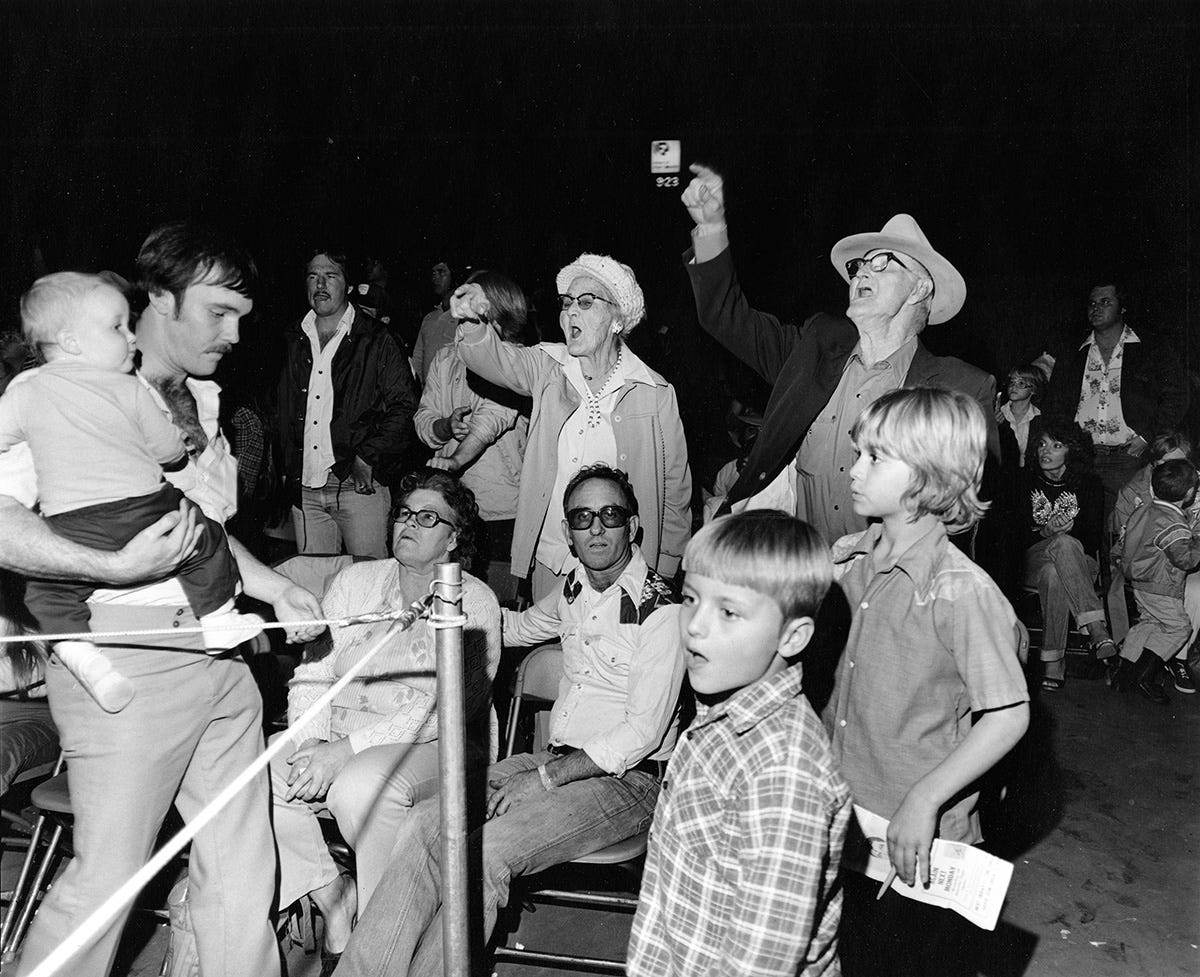

During his three decades as a competitor, Mantell, who now serves as president of the Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame, developed a keen understanding of wrestling’s cultural significance. “Wrestling was a sport that was very much built around this idea of good versus bad,” he tells me. “During the 1980s, there was an intimate level of audience interaction. It was a show marketed to the common man, with low-priced tickets that anyone could afford. People would come to the shows, and they would be right up in front of the action, yelling and screaming at the wrestlers they hated and blowing kisses to the ones they loved.”

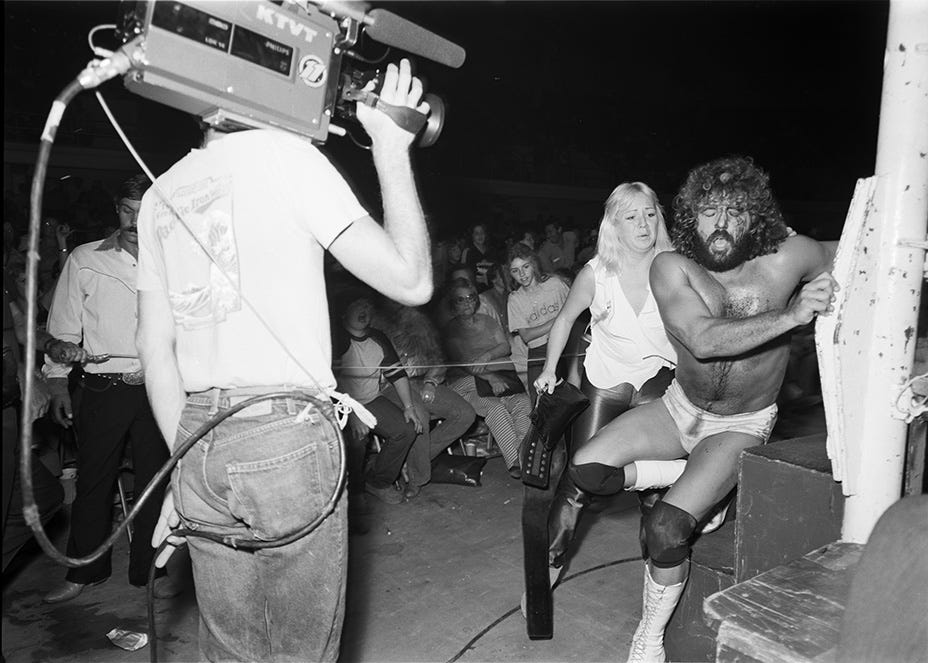

The in-ring work, he explains, consisted of a delicate improvisational challenge, with the competitors coordinating their efforts as they tried to stay attuned to minute shifts in the energy of the audience. “It was crowd psychology, and you only had your bodies and — when you were cutting a promotional spot or doing an interview — your voices to sell your work, to get over.”

I’ve known Mantell for nearly three years, during which time I’ve become acquainted with his ability to deliver off-the-cuff remarks, engage in tough-guy banter with radio and television hosts, and motivate large assemblies of people. “When you think about it,” he says, “the kind of education I got from wrestling helped me develop a bunch of skills that are really useful for the world we’re living in. And when you realize I was just some jock kid from rural California, well … I don’t know that there’s a better way to learn how to use your body and your personality to relate to people. Today you see the young wrestlers coming up in the business and they have acting coaches and all that, but, 30 years ago, you were on your own unless you, like me, lucked into meeting a mentor like Roddy Piper. Roddy was one of the best heels of all time, but as far as my character went, I guess I was usually a good guy, a babyface — it came naturally to me.”

HOW REAL IS WRESTLING?

The election of 2016 was framed as a contest between stock wrestling types: an inexperienced but flashy bad guy, his lack of qualifications and rudeness of manner highlighted in every single one of the innumerable news stories about him, challenging an uncharismatic but skilled policymaker who had toiled for four decades in the hope of earning a shot at the world title.

Or was it? That would certainly prove to be the dominant story for mainstream publications such as the New York Times and the Washington Post. “We forget that not everyone is rooting for the same performer,” explains Eero Laine, a professor of theatre at the University at Buffalo and one of the editors of the essay collection Performance and Professional Wrestling. “A substantial number of people, though obviously not the majority of them, were rooting for the Ric Flair character, the tell-it-like-it-is jerk who promises to win at all costs.”

At any rate, with President-elect Donald Trump hogging the national spotlight thanks to viral tweets and a cabinet selection process redolent of the WWE “brand drafts” that place wrestlers on either the RAW or Smackdown weekly shows, wrestling fans can be forgiven for posing the same question that writer Jeremy Gordon tried to answer back in May: “Is Everything Wrestling?” In an essay for the New York Times Magazine, Gordon argues that anybody even halfway in the public eye is busily moving himself or herself “around on a narrative chessboard, [their] every move calculated to advance a maximally entertaining storyline.” He isn’t alone; several other writers have rushed to compare Trump’s style to that of a classic wrestling bad guy. Gordon’s take, however, is among the more nuanced of the many “Trump and wrestling” opinion pieces to appear thus far, covering a lot of ground. Yet Gordon persists in maintaining that the performance and the commercial reality behind it are different things. There is an outward display — the wrestler preens and struts before the crowd — and then there are the backstage maneuverings that have led to the wrestler winning or losing his match.

Wrestling theatrics (which involve wrestlers attempting to show us how they and their employers want the match to be experienced) and political optics (which involve positioning candidates in various self-aggrandizing ways) make it easy to lose sight of the fact that each type of performance has distinct consequences. Even seemingly experienced observers who remain mostly external to these processes, watching and commenting, can wind up confusing their impressions of performers’ intentions (“Trump is just toying with us; he’ll drop out in a week!”) with the outcomes of their performances (Trump wins).

This was a major problem with the fan-run “dirt sheets,” on which smartened-up fans depended for gossip and analysis during the 1980s and ’90s. These publications, the most notable of which was Dave Meltzer’s Wrestling Observer Newsletter, occupied a space similar to that filled in the political arena by FiveThirtyEight, Vox, and Politico: delivering seemingly endless speculation, sometimes informed by insider information, about the front office machinations of a spectacle greedily consumed by obsessive fans. Many readers of the dirt sheets viewed insider information as their ticket to a heightened enjoyment of the sport, but an obsession with firings, hirings, booking decisions, and television ratings could sometimes obscure the fact that there was an actual show to watch.

“All this discussion of real and fake is unhelpful for understanding wrestling,” says Broderick Chow, a lecturer in theater at Brunel University–London and one of the co-editors of Performance and Professional Wrestling. “The performance is an ‘action’; it happens. You could go down that same path with Trump and the American political situation. Are his tweets meant to distract; is his transition mismanaged? That’s irrelevant. What is relevant is that he is now the president-elect of the United States. Better to consider the maneuvers he used to get there, and the strategies for resisting him and defeating him.”

Chow continues: “Look, take the elections: Experts are writing so-and-so has a 40 percent chance of winning, or a 30 percent chance of winning, or whatever. But is this the same as explaining, ‘Here is the how the political campaign has been organized in a state or county’? No; nor does guessing which performer the WWE promoter Vince McMahon will ‘give’ the title to help us understand how the wrestlers work a match or manage crowd reaction. The election was an action; it happened. The mainstream media had their narrative, and alternative media had their own narrative, and neither explains the outcome.”

VIOLENT CHARACTERS AND VIOLENT LANGUAGE

Trump winning an election that garnered incredible ratings wasn’t the pay-per-view culmination of a meaningless feud, at the conclusion of which the TV media and the president-elect can simply reboot the continuity and start afresh; instead, it was yet another traumatic event that indicated how bitterly divided the country had become. Trump, however, has made a number of attempts to pivot in a new direction: talking about unity in his victory speech, addressing the nation with a heartfelt Thanksgiving message, waxing rhapsodic about our “shared sacrifice” during an appearance at the annual Army-Navy game.

Consider the juxtaposition of “face” Trump, now trying to market himself as the great conciliator, with the brash “heel” Trump of reality TV, enemy-baiting rallies, and raging tweetstorms. This is strange and uncomfortable territory for people accustomed to politicians who conduct themselves with more dignity and reserve; casting oneself as magnanimous in victory and a friend to all Americans, then retweeting shitposts and memes from random teenagers, doesn’t seem especially presidential. This rapid-fire metamorphosis might be understandable if, say, Trump were merely reinventing himself in the manner of a pro wrestler, transitioning from the “Real American” Hulk Hogan to his villainous “Hollywood” Hogan and then, angle concluded, back again.

Yet no obvious separation exists between Trump’s public and private selves, much less his back-slapping cordiality and his knee-jerk fury. He is always on, and always subject to an outburst of violent anger, so does that mean he is always himself? A caricature of himself? “Do I live in character 24/7? No way. Sure, there have been a few guys who got lost in their crazy gimmicks,” Mantell says. “And it’s true that a gimmick — meaning who your character is as a wrestler — is often your own personality with the volume turned up. At the end of the day, though, most of us turn it down or turn it off. Wrestling was a way to pay the bills.”

In other words, wrestling wasn’t life lived as some kind of larger-than-life character; it was a way to make a living. And these workers were vulnerable, both in body and spirit. This is the essential point that Dan O’Sullivan sought to make in “Money in the Bank,” an essay for Jacobin that presented the history of wrestling as a story primarily about worker exploitation, hostile corporate practices, and crippling injuries. For O’Sullivan, the flashy personalities and memorable feuds that dazzled the fans were nothing more than a smokescreen obscuring the somatic toll of an unregulated sport played by uninsured athletes whose career prospects amounted to working for the national conglomerate or toiling in relative obscurity for TNA, Ring of Honor, or any of the countless other under-capitalized independent promotions around the country.

“Is wrestling real?” Mantell asks. “Well, let me see — 10 knee surgeries, they’ve rebuilt my shoulder, my ankle. Concussions? I can’t even tell you how many concussions I’ve had. I’m part of a concussion study group, as are lots of other guys who were in the business.”

And not only are the injuries real; the rhetorical violence is too. People who are triggered by fictionalized depictions of rape, horrifying Asian-American stereotypes, or transphobia should avoid much of the late-1990s WWE product (a scene involving African-American powerlifter Mark Henry reacting to the revelation that his storyline love interest Chyna has tricked him into having sex with a transgender woman is especially loathsome).

“2016 has been a year of violent words,” explains Claire Warden, a senior lecturer in drama at De Montfort University and a co-editor of Performance and Professional Wrestling. “The violence of those words has been all too apparent. My thoughts come out of reading the work of gender theorist Judith Butler, particularly her claim that language is violent. Language does not just describe a situation or provide a bit of background narrative — it actually is violent.”

In Warden’s opinion, the language of the physicalized pro wrestling world works as forcefully and as brutally as a well-timed suplex or tombstone piledriver. “Listen to advocate Paul Heyman repeat the name of his client — ‘Brrrrock Lessssnarrr’ — or The Undertaker slowly and methodically threatening his opponent to ‘Rest in Peace,’ and you’ll get the sense that performed words can be innately violent,” she continues. “The president-elect and his vocal followers seemed to use the former’s old adversary — and WWE owner — Vince McMahon’s famous catchphrase as a model: the gleefully malevolent and violently dictatorial ‘You’re fired.’ In 2016, the violent language of pro wrestling seems to spill out under the ropes and into politics.”

Eero Laine echoes Warden’s assessment of Heyman’s acting chops. “It’s actually a little surprising to me that no politician has tapped Heyman, who I probably don’t need to even say is the best promo guy in the business, for their political campaign,” he says. “I don’t know Heyman’s politics, but if you want to sell something, go get Heyman. I’m coming at this from the perspective of theatre and the way that representation, theatrical representations in particular, function in a global economy. Pro wrestling has really only hesitantly been included in theatre — it has been called theatrical, of course — but I’m certain we have to place pro wrestling squarely in the realm of globalizing commercial theatre.”

Pro wrestling is a form of labor — and extremely hazardous labor, at that — in an industry where the prospects for a lengthy career are dubious at best. The wrestling performance constitutes a particular kind of global theatrical spectacle, and this performance, though scripted in advance, is an action with consequences. Every part of it, even the language employed by the wrestlers and TV commentators, is concerned with delivering a violent, gut-wrenching impact. But how does wrestling itself evolve? Is the sport, as many would argue, always ahead of the pack and able to serve as some great source of cultural innovation? Has it helped shape the present, its politics and stylistics, that we all share?

‘IT’S A RIGGED SYSTEM!’

Attorney Grey Pierson, who operated the Dallas-based Global Wrestling Federation during the early 1990s, emphasizes that wrestling, far from shaping the culture, has usually reflected and magnified certain aspects of it for profit and theatrical effect. “Wrestlers are among the finest actors I’ve ever seen,” he says. “They operate on a stage without any kind of true demarcation between them and the crowd, and they tell a story that, in my opinion, has always had an intrinsic appeal to children and people of lower socioeconomic status.”

Pierson, who has devoted a lifetime to untangling complicated legal transactions, views the world as anything but black-and-white. “Nevertheless, when it comes to wrestling, you have to tell this simple story,” he explains. “Heck, wrestling was a hit on early TV because a studio only needed one camera to record a halfway decent film of it: It was all about simplicity! And, as far as the narrative goes, you have the good guy, the face, who is always the best trained and best prepared … why does he lose? Because it’s rigged, because the bad guy cheats. This resonates emotionally with an audience of people who feel weak and oppressed — it’s a rigged system! Even if you and I know that it’s not this way, that’s the story that sells.”

Wrestling has always had its share of stock villains. Vicious African savages, mad Russians, sinister Soviets, illiterate hillbillies, sadistic Nazis, and their ilk have been a part of the sport’s history since the early 1930s. These were bad guys whose stock-in-trade consisted of evoking audience fears of the menacing Other. Even seemingly sui generis creations, such as the vicious but effeminate Gorgeous George and the flamboyant, androgynous Adrian Street, generated audience heat by forcing fans to confront an ill-fitting gender binary.

“A good storyline uses the news, events happening in the news. We did excellent business with an angle about the big, and, in retrospect, probably exaggerated, battle between domestic car manufacturers and their Japanese competitors,” Pierson says. “You take something that has many complicated explanations and have the wrestlers, through their performances, boil it to down to the level of pure emotion, and after that it speaks volumes to the target audience.”

What Pierson describes does sound a great deal like what Trump has accomplished. But though many modern wrestlers have done an excellent job making such emotional appeals, and Trump himself has participated in wrestling and reality TV, both realms of performance are merely evolved versions of carnival hucksterism. Professional wrestling, after all, emerged from its humble beginnings as a carnival sideshow, at which the tout tried to trick local rubes into giving him their hard-earned cash for a chance at having their legs broken by the tout’s tough shooter. This matter of parting fools and money isn’t unique to the wrestling tradition; it is, rather, part of the sales and marketing tradition that constitutes the greatest (and perhaps only!) intellectual bequest of the U.S. to the rest of the world.

Trump masterminded a scorched-earth sales job, desperate to scrape every doubloon and vote out of the Rust Belt before that market ceased to exist, and now he has a chance, in wrestling parlance, to “burn down the territory.” This term refers to the practice of certain short-sighted promoters who, far from growing an audience in an organic way, utilize the basest appeals to inflame fan sentiments. The classic example of this, used sparingly for obvious reasons, is to have a redneck wrestler address an all-black audience in the American South and berate them with a torrent of racial epithets. The result, at least at first, might be improved ticket sales, but the final outcome is often nothing short of a full-blown riot.

Once again, this isn’t unique to wrestling. Think of Enron, think of Bernie Madoff, think of Countrywide Mortgage. The goal of the sales game, for players going the cheap and dirty route, is to steal as much as one can steal before being forced to choose between facing the music and drinking the hemlock. Yes, we have seen examples of this in wrestling, and yes, Trump and some of his most vocal followers have perhaps borrowed a certain kind of masculine swagger from watching the towering titans of the 1990s trade taunts and toeholds. That’s an interesting something, but it’s not everything — and it’s far from the most important thing worth understanding about the wrestling business.

COMMUNITY AND BROTHERHOOD

When I consider the deeper meaning of professional wrestling, I recall the time Mantell brought me to Red Bastien’s Shootout, an informal gathering of current and former wrestlers in the Dallas area. Founded by the late Bastien, who was famed for his in-ring skills, impressive red mustache, and eye for talent (he discovered and helped train 1980s wrestling icons Steve “Sting” Borden and Jim “Ultimate Warrior” Hellwig, among others), the event offered a chance for grapplers such as Brian Adias and “Killer” Tim Brooks to eat barbecue, drink beer, and reminisce about lives that intersected on the road and on the mat.

This kind of labor-forged bonhomie, shared by athletes of all races, genders, and sexual orientations, is the one verifiable positive result of American pro wrestling. Like the stooped-over coal miners who would gather at the Slovak Club in my southwestern Pennsylvania hometown, these workers had been forced by decades of proximity and collective effort to develop a grudging respect for one another. They referred to each other as “brother,” a ubiquitous bit of wrestling slang made famous by Hulk Hogan by way of “Superstar” Billy Graham (who himself borrowed it from the world of evangelical religion) that is now used by nearly everyone in the business and applied to wrestlers of all genders. They were brothers; they had shared a struggle; and now they struggled to maintain what was left of a community ravaged by far too many premature deaths.

“Back in the 1980s, there were no gates and guard rails between me and the fans,” Mantell says. “I would sign autographs and talk to everyone, people from all walks of life. The beauty of the business back then was how personal it was, how I got to travel everywhere and talk to all these people, whether I was in Japan or Israel or wherever. I didn’t walk out there and hurl racial epithets at people and build a lot of cheap, dangerous heat. No, I wanted to honor the crowd and the community, and give them their money’s worth, because they paid me to play a game in front of them.”

“Togetherness and brotherhood: That’s what wrestling was all about, man,” Mantell continues. “And when I get to thinking about how things are now, I wonder: Wouldn’t the country be in a better place if it were still like that, if we could bond in such a close and meaningful way? Maybe politics is like wrestling, the edgier wrestling we watched in the 1990s and 2000s, but it sure isn’t like the wrestling I spent 30 years doing.”

You can read the subsequent article on this topic, which I wrote for UnHerd in 2023, by clicking here. Alas, it met the same ignominious fate: people looked at the HED and DEK, skimmed a few lines, nodded their heads, and assumed I was saying the opposite of what I had written. I later saw that a book I was reviewing for the Washington Examiner cited that article for the purposes of claiming “Pro wrestling explains Trump.” Folks…it doesnt!!!

When republishing my content, I make a point of removing all the overwrought “Trump is a baddie” stuff that was inserted into these articles by even the most well-intentioned of editors. In the interest of full disclosure, such stuff is editorial CYA — if you thought Trump was a bad boy, you didn’t need incessant reminders of the same, and if you loved him with all of your heart, too many lines like that would cause you to stop reading a piece you might otherwise be enjoying.