You have seen the creativity seminars. They are everywhere now - in hotel conference rooms, on webinars, in airport bookshops. They promise to unlock your "unique genius," to help you "think outside the box," to teach you the "seven habits of highly creative people." The price varies but the message does not: Buy this book, attend this workshop, follow this system, and you will become original. But here is what they do not tell you: Everyone else has bought the same book.1

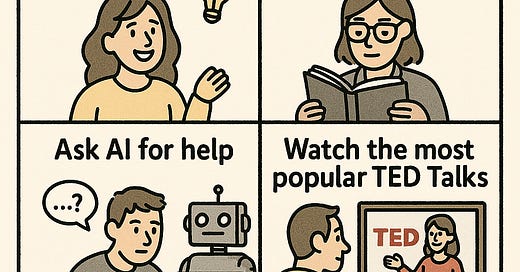

The creativity industry operates on a simple premise. They tell you that originality can be packaged, systemized, and sold. They have turned independent thought into a franchise operation, complete with training manuals and trademark disputes. Consider the standard workshop formula: First, they show you pictures of famous "innovators" — Jobs, Einstein, Picasso, Ye, Musk, Progressive Flo. Then they extract principles from these lives, reducing complex human beings to bullet points. Finally, they sell you these bullet points in various formats: books, online courses, weekend retreats. It is a remarkable achievement, really. They have found a way to mass-produce uniqueness.

The irony is lost on no one except most of the participants. Here they sit, in matching conference chairs, drinking the same weak coffee, taking notes on identical legal pads, all learning how to be different. Together. The facilitator tells them to "break the rules," but only after establishing a very strict set of rules about how to do so. They learn to "think differently," but only in the prescribed manner. They practice "disruption," but on schedule and with proper supervision. This is creativity as conformity, rebellion as routine. It is the corporate version of wearing your baseball cap backwards — a gesture of defiance so standardized it appears in dress codes.

But perhaps this is how it has always been. History likes to tell the same stories in different costumes. The creativity gurus are right about one thing: There is nothing new under the sun. What they fail to mention is that this includes their own teachings. Read any of these books and you will find the same examples: the Post-it Note invention story, the Apple "1984" commercial, Thomas Edison's shopworn quote about perspiration and inspiration. These stories are to creativity seminars what "Wonderwall" was to guitar stores in the 1990s — inevitable, inescapable, and increasingly meaningless through repetition.

Now we have entered the age of hot takes about AI, and the conversation about originality has taken on a new dimension. The same people who once previously pimped hands-on creativity workshops now issue dire warnings about AI stealing our creative jobs or offer new seminars on "how to stay creative in the age of AI" or "hacking AI to unlock your creative juices." Once again, they have found a problem they can solve for a fee.

The Work of the AI Author

They say a new contraption can change the world overnight. Once upon a time, folks talked about the radio in that excited tone, and then they gave the television and the Atari 2600 that same breathless, confused tribute. Now the talk is about AI.

What these experts miss is the simple truth: AI has not changed the fundamental nature of creativity; it has merely revealed it. Creativity was never truly original; it was always recombination, synthesis, transformation.2 The painter takes from other painters, the writer from other writers, the musician from other musicians. AI does the same thing, just faster and more obviously. It is a mirror reflecting our own creative process back at us, and many of us do not like what we see.

The backlash against AI-generated content often comes from the same quarters that once sold us the myth of pure originality. They call AI outputs "derivative" or "soulless," as if human creativity emerged from a void rather than from our collective cultural heritage. They insist that only humans can be truly creative, conveniently ignoring how much of human creativity involves imitation, adaptation, and remixing3 — the very things AI excels at.

The Work of Bad AI Output

The computer doesn't care if you're a numbskull. That's what makes it dangerous. The GIGO principle existed long before Alan Turing was potty-trained. Feed it garbage questions, it spits back garbage answers with the same straight face. A data scientist I know complains her AI assistant fabricates numbers in spreadshee…

The champions of AI, meanwhile, celebrate its ability to democratize creation. Anyone can now generate an image, compose a melody, or write an essay without formal training. But in this new landscape of push-button creativity, we find the same old problem: uniformity disguised as innovation. Everyone uses the same tools with the same settings to produce variations on the same themes. We have not escaped the paradox; we have only automated it.

There is a third way, though — neither rejection nor surrender, but considered use. Some have begun to use AI not as a replacement for human creativity but as a prosthetic, an extension of it. They treat these tools as they would any mechanical keyboard or set of fine brushes — with skill, discernment, and purpose. They understand that the value lies not in the tool itself but in how it is wielded, not in what anyone can do with it but in what only they would think to do with it. The originality is not in the medium but in the vision. This approach requires neither the pretense of pure originality nor the abdication of the creative process. It requires only honesty about what creativity has always been: conversation rather than monologue, inheritance rather than invention.

The real innovation of the creativity industry is not teaching people to think originally, but convincing them that they need to be taught in the first place. As I mentioned earlier, they have created a problem so they can sell the solution — now that’s creativity at work! In earlier times, people simply did their work — painted their pictures on cave walls, memorized their lyrical tales, built their herds of sheep and cattle — without first attending a seminar on how to do so.4 The idea that creativity requires certification would have seemed absurd to them. Now it seems essential. We have reached a point where people are afraid to think without instruction, to create without permission. The creativity industry has done to original thought what McDonald's did to hamburgers: standardized it, packaged it, and convinced too many people they cannot make their own.

The professionals of originality face a peculiar problem. Their business model depends on originality being both teachable and rare. If everyone can learn it, it is not special. If no one can learn it, they have nothing to sell. So they walk a careful line, promising unique results from universal methods. They offer "personalized" programs with standardized content. They guarantee "breakthrough thinking" using techniques that millions have tried before. It is a con game, but an honest one. Everyone involved knows the truth: These seminars do not create creativity any more than diet books (or influencers selling diet books while taking weight loss drugs) create weight loss. What they create is the feeling of doing something about the problem.

But perhaps I am too hard on the creativity industry. After all, they are only giving folks what they want: simple answers to complex questions, haven in a heartless world that wants nothing to do with them, the comfort of knowing that there is a system, even for being unsystematic. And perhaps this is the best we can do. Perhaps true originality was always a myth, and all we have ever done is put our own spin on old themes. Perhaps the creativity seminar, with its recycled wisdom and manufactured insights, is the perfect symbol of human innovation: derivative, commercial, and somehow still capable of inducing the majority of participants it’s worth remaining on this side of eterntiy.

History does repeat itself, but never the same way twice. Each generation rediscovers the same truths, makes the same mistakes, has the same insights — but believes they are doing so for the first time. This is not failure; it is human nature. The creativity industry understands this. They know they are selling old wine in new bottles, but they also know that each customer needs to believe their bottle is unique. It is a kindness, really — allowing people to feel original while following a script.

Seminars aside, we are all doing a version of the same thing: taking what came before, adding our own touches, and passing it on. The creativity seminar is no different from the Grecian urn or the sonnet or the AI prompt — it is humanity's endless attempt to say something new about something old. And while that’s not some grand thesis, it is the tea, sis. Stop overthinking it and start doing the work.

The Work of the Professional Writer and the Writing Teacher

On the contrast between doing the work and preparing to do it

“You made all this money just from your creative work?”

“Yes, just from selling you this book on how to do creative work.”

My longtime acquaintance Noah Berlatsky got some things right in his 2018 Splice Today essay about not thinking for yourself. He correctly identified the social nature of knowledge and the impossibility of being an expert on everything. But he swung too far in the direction of trusting expertise uncritically. His piece ultimately substitutes one simplistic formula ("always think for yourself") with another equally flawed one ("always trust the expert consensus"). He fails to address who decides who the experts are, how expert consensus can be wrong or corrupted by political and economic forces, and the difference between technical knowledge and value judgments.

He correctly notes that we learn from others, but doesn't distinguish between thoughtful deference to expertise and mindless submission to authority. In his rush to deflate contrarian individualism, he ends up championing a conformism that's perhaps even more dangerous in its own way. The truth, as usual, lies somewhere in between — we need both independent critical thinking and the humility to learn from others. Neither complete individualism nor complete deference is the answer, whatever “answer” even means in this context (an either/or almost as silly as this one). We play the imitation game to learn how to do the work, but the output is ours alone.

Remixing presents a problem all its own, but the work of someone like Greg “Girl Talk” Gillis is fascinating nonetheless.

Long apprenticeships and complicated initiations were par for the course, but that’s something very different than “hacking” the work of Titian’s studio in a weekend. Even Pittsburgh’s Andy Warhol(a), the greatest of avant-garde commercialists, paid his dues at Carnegie Tech and then in the greeting-card industry.

Creativity is knowing when to look inside the box, as well as outside of it.

I have found the best use of ChatGPT to be naming acronyms. No longer will we have to have a Washington D.C. Intern burning the midnight oil to make the find the right letters to make the PATRIOT Act.

Instead, suggest the acronym you want, describe the project in enough details, and ask for 10 options.