The Work of the Professional Writer and the Writing Teacher

On the contrast between doing the work and preparing to do it

The professional writer sits at his desk every morning, hammering away at his loud-as-hell mechanical keyboard, while the writing teacher stares at a blank screen on his fancy, distraction-free writing device.1 The writer files copy and cashes checks. The writing teacher conducts seminars on how to write a book he has never written. These two men went to the state university together and are still the best of friends.

The professional writer works in his small house in the city. He works a day job writing corporate research content and in his spare time churns out stories, columns, essays, and pieces for whoever will pay. He has been at this for twenty years, and his output is measured in thousands. A small library could be filled with what he has written. He doesn't talk about process or inspiration. He talks about deadlines and word counts.

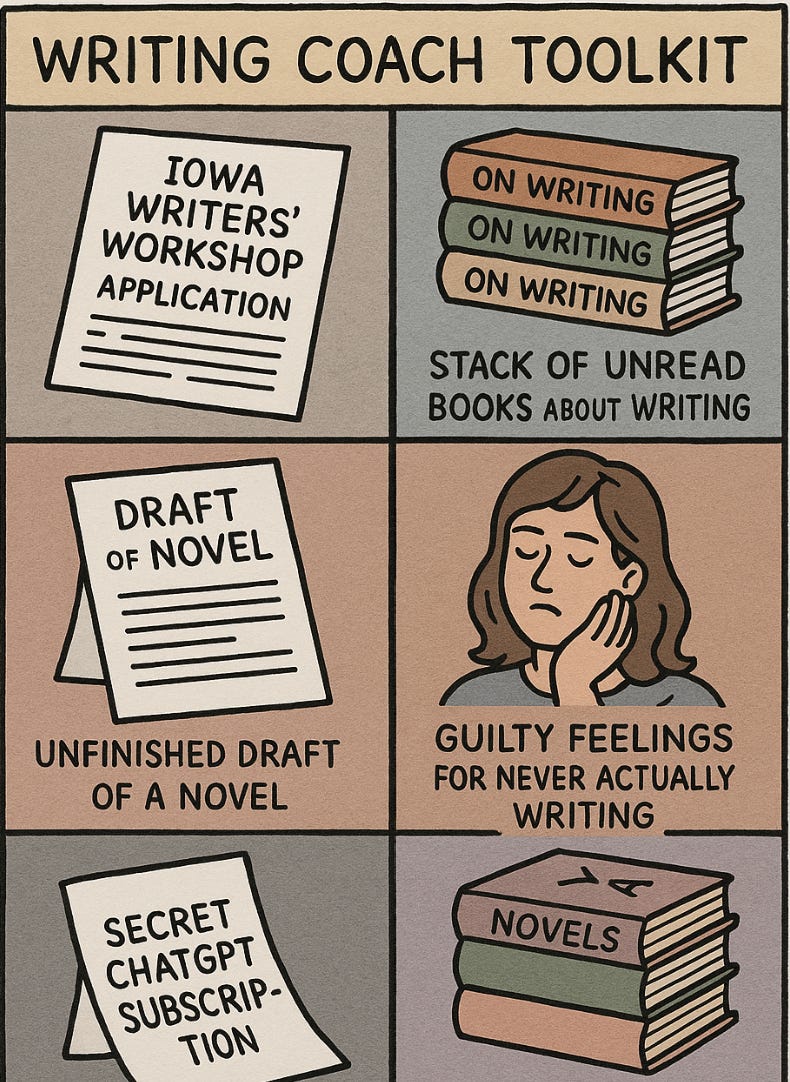

The writing teacher has coached others for nearly as long. He has developed elaborate theories about style, editing, and the craft of storytelling that echo the theories of past writing teachers. He has built a career explaining to other would-be writing teachers how the teaching of writing should be done. His blogs about writing have attracted the attention of hundreds of aspiring writing teachers. His workshop sessions have drawn students interested in careers that will be spent giving workshop sessions to up-and-coming versions of themselves.2 But when asked about his own book, he speaks in the future tense. It is always coming, never here. He just needs to write the perfect proposal, find an agent, and so on.

The professional writer bangs out an inexplicably good article — he has no idea why it lingered in the mind of the reading public, yet linger it did — and receives solicitations from book agents, rather than the other way around. He contributes to anthologies, edits manuscripts for others, and ghostwrites entire books when the money is right. He has written in hotel rooms, airport lounges, and hospital waiting areas. He never speaks of inspiration. He speaks of putting words on the page until they add up to something that can be sold.

The writing teacher has quit many jobs. He has walked away from college composition classes and magazine staff positions. He has abandoned copywriting gigs and corporate communications roles. The reason is always the same: he needs time to work on his book, the one he has been planning for years. The book remains unwritten. The planning continues.

Last week, the writing teacher admitted something to the professional writer. He said he hates writing. He hates the process of putting words on the page. What he loves is the thought of having written. He dreams of the finished product sitting on the shelves, without enduring the labor of production. And all he has written so far is advice about writing.

The professional writer empathizes with Ronnie Coleman, the now-debilitated bodybuilder who said, "Everybody wants to be a bodybuilder but don't nobody want to lift those heavy-ass weights." Coleman lifted the weights — ridiculous weights, powerlifting loads at bodybuilding volumes — until he couldn’t lift anymore. He didn't just talk about lifting them. The professional writer is the same way. He doesn't just talk about writing. He writes each story like it’s his last. After all, if he can go, he can go today.

Ernest Hemingway once said of columnist Jimmy Cannon that Cannon wrote "to end writing" with each new column.3 This is how the professional writer approaches his work. Each piece is meant to be definitive, to say what needs saying and nothing more. He doesn't save ideas for later. He doesn't hoard sentences for some future masterpiece. He puts everything he has into what he is writing right now.

The writing teacher hoards his ideas the way the dragon Smaug hoarded his dwarven gold. He keeps notebooks full of concepts. He builds outlines that never become paragraphs. He talks about his book in the same way a man talks about the fortune he will make someday. It exists only in the subjunctive mood, in the realm of "would" and "could" and "should."

The professional writer doesn’t care about the subjunctive mood or the pluperfect tense, even if he grasps their application deep in his bones. He has learned that inspiration follows action. He sits down to write whether he feels like it or not. The words come because he demands they come. Some days the words are good. Some days they are not. But they are always there, and he always gets paid for them.4

The writing teacher waits for inspiration. He believes in the shining moment, the ideal circumstance, the right mental state. He thinks the conditions must be perfect before he can begin. He has been waiting for twenty years. The conditions have never been perfect. The book has never been begun.

The difference between these two men is not talent. It is not intelligence. It is not education or opportunity. The difference is that one of them does the work and the other talks about doing the work. One lifts the weights and the other describes how weights should be lifted.

The professional writer does not think of himself as an artist. He thinks of himself as a craftsman. He makes things with words the way a carpenter makes things with wood. The quality of his work varies, but the quantity never falters. He produces.

The writing teacher sees himself as an artist awaiting the perfect moment of creation, an attendee of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop taking it one sentence at a time. He believes in genius and inspiration. He thinks of writing as a mysterious process that cannot be forced or scheduled. He waits for lightning to strike. The sky remains clear. In truth, he is not so much dependent on predictions of weather but on whether he will find the intestinal fortitude to do anything at all.

There are days when the professional writer hates what he does. There are mornings when the blank screen looks like a prison cell. There are afternoons when each sentence feels like digging a ditch with a teaspoon. But he continues to dig. By evening, the ditch is dug. The story is filed. The check will come — and if it doesn’t, he will demand it until it does.

The writing teacher has innumerable justifications to offer for why his book remains unwritten. He blames his jobs, his schedule, his obligations to friends and family. He speaks of burnout and creative blockage. He must rewrite each sentence a thousand times before releasing it to a world in which perhaps ten people will read it more than once.

Twenty years have passed. The professional writer has produced volumes. The writing teacher has produced excuses. Both men have spent the same amount of time in the same profession. One has written. One has talked about writing.

What the writing teacher doesn't know is that the professional writer also dreams of writing a great book someday. But while he dreams, he writes. While he plans for tomorrow, he produces today. That production represents the rough draft of his book of hours — each published success another sand in the hourglass measuring the days of our lives — and it is always being iterated upon. His dreams and his actions move in the same direction. The writing teacher's dreams and actions are at war with each other.

The professional writer is a hedgehog who knows that writing is work. It is not magic. It is not mystical. It does not require years spent in workshops, telling other would-be writing teachers to "keep going in that direction." No, it is sitting in a chair and putting words on a page until you have enough words to submit your story and then your invoice. Sometimes those words sing. Sometimes they trudge. But they are always there, marching across the page, earning their keep. Escort enough of those words to the pay window, grab the cash on the barrelhead, and that chair can be upgraded to a Herman Miller offering.

The writing teacher is a fox who knows many things about writing. What he doesn't know is how to face the empty page day after day, filling it with words that may or may not be good, words that must be written regardless of their quality because the only way to write is to write — the only way out is through.

"Ain't nothing to it but to do it," Ronnie Coleman used to remind us. The professional writer understands this. The writing teacher does not. And that has made all the difference.

Before you go, check out Dominic Tanzillo’s excellent follow-up to my essay about small talk. Dominic focuses on the value of small talk as it relates to a doctor’s bedside manner and clinical effectiveness.

The essay you're about to read is a lyrical exploration contrasting doing with preparing to do. It should be taken as the perspective of a man of action — someone who “does the work” — rather than the final word on writing education.

I want to acknowledge that teaching composition and storytelling structures absolutely have their place in our literary ecosystem. The Iowa Writers' Workshop has produced extraordinary talents like Flannery O'Connor and Raymond Carver (though Carver, a mediocre student, did not finish the program and his hand was guided to a considerable extent by the red pen of Gordon Lish), and seminars by Robert McKee and others have helped countless ink-stained wretches find their voice and hone their craft.

What I've attempted to capture here is not an indictment of writing education, but rather the tension between endless preparation and actual production. Both have value. Both serve purposes. But as with any craft, there comes a point where theory must give way to practice.

Oh, and while you’re hanging out down here in the footnotes, you should check out my article about Jordan Peterson and online anonymity that appeared in UnHerd yesterday, which is an elaboration on this piece on anonymity from 2023 and another from last year. I also wrote a fun one about possible “outside-the-box” papal candidates for Splice Today.

So it goes.

Of all the great columnists — the Runyons, the Heinzes, the Red Smiths — Cannon is my favorite, the absolute GOAT. When you read an esasay like this, you’re reading him channeled through me — the best of what I’m capable of producing in spite of lacking both “world enough” and “time.”

Or else, as I discussed in this CJR article.

This is so funny. In nursing terms. You put your back into it.

Yesterday afternoon, it was a teaspoon. Good to have the reminder to keep digging.