The Work of the Worst Article I Ever Wrote

Reflections on a stray Teen Vogue byline that contains perhaps 10% of my own writing

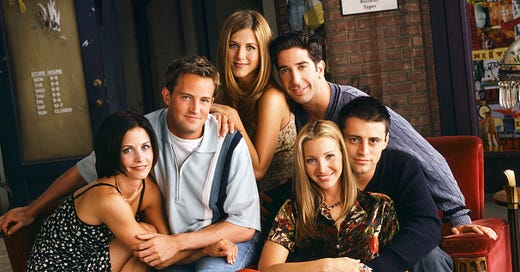

The nice editor at Teen Vogue wanted an article about old TV shows. She said the kids were upset about Friends and Seinfeld. The jokes were mean. The characters were white. Everything was wrong with everything that came before.

I told her I'd write about time. About how every generation thinks it invented decency. How the young always believe they're the first to notice cruelty. But that wasn't what she wanted, even from a "certified"/"credentialed" historian.

The check would be $150. For a year's work, back and forth, draft after draft. By the time it saw print, maybe ten percent was mine. The rest was what somebody thought teenagers needed to read. Safe outrage about safe targets. Old shows nobody was defending anyway.

I wanted to tell them about 1967. About the kids who thought their parents were squares. Who burned draft cards and grew their hair and said they'd never become what they hated. Those kids are grandparents now. They vote Republican. They complain about pronouns and pink-haired enbies.

I wanted to tell them about 1932. About the brave young communists who saw capitalism dying. Who were sure the inevitable revolution was coming. Who knew which side of history they were on. They died believing in Stalin or they died believing in nothing.

But the editor wanted Ross Geller. She wanted problematic. She wanted the kids to feel good about being better than a sitcom character from 2002.

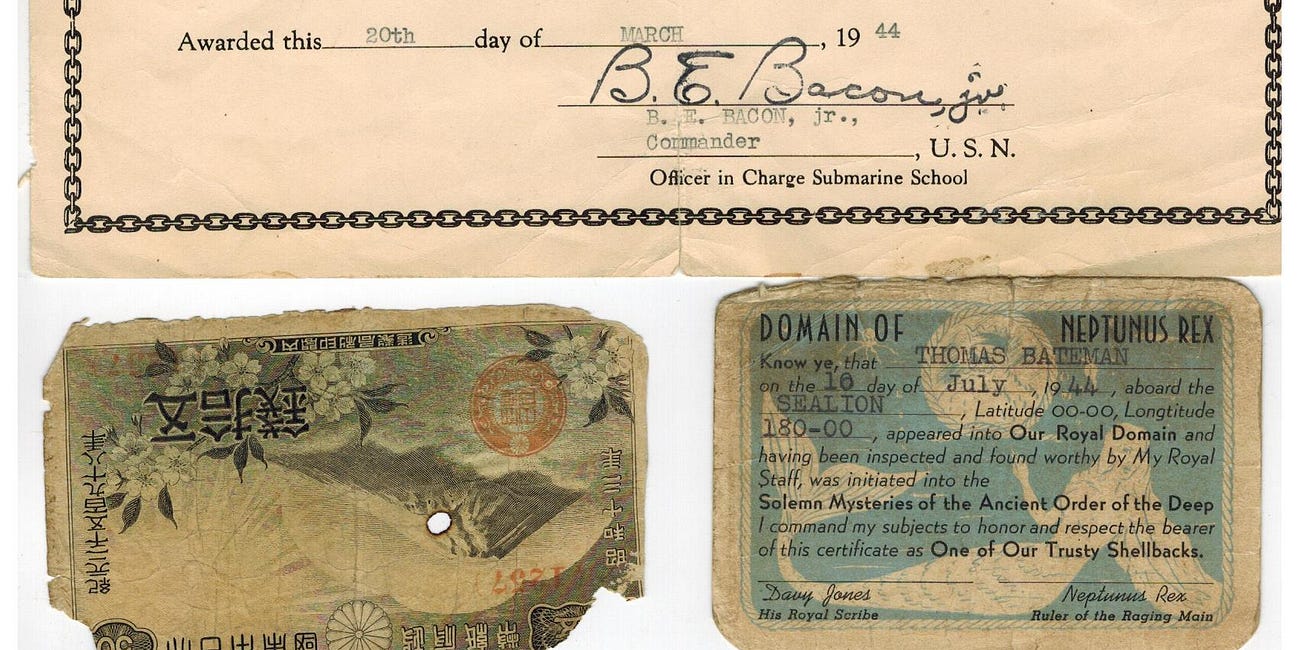

My grandfather worked in a steel mill. He told off-color jokes. He hit his kids and his wife way too hard. He drank way too much. He also fed his family through the Depression. He fought in the Pacific, helped kill 3,000 people, half of them our allies. He built a few things that lasted. Was he a good man or a bad man? Depends when you ask.1

My uncle thought my grandfather was backwards. Uneducated. Brutal. My uncle went to college, grad school, the Foreign Service. He read books, learned languages, saw the world. He never hit anybody. He also never built anything. Spent his life in meetings, talking about talking. Was he better than his old man? Depends what you measure.2

The kids writing for Teen Vogue think they've figured it out. They see the sexism in old shows. They count the white faces. They notice who's missing. They're not wrong. But they're not special either.

In 1919, young writers were horrified by Victorian prudishness. In 1955, they were horrified by McCarthy. In 1980, they were horrified by Reagan. Every generation gets its turn at being horrified. Every generation thinks it's the first to see clearly.

The French have a phrase: autres temps, autres mœurs. Other times, other customs. It means what seemed normal then seems strange now. What seems normal now will seem strange later. It's not progress. It's just change.

But try explaining that to a 23-year-old editor who knows she's on the right side of history. Try telling her that history doesn't have sides. That it's just one damn thing after another, and everybody thinks they're the hero of the story.

The article she wanted was about old TV shows being problematic. About how we know better now. About how the kids watching Netflix can spot the sexism their parents missed. It's a comforting story. It makes the young feel smart. It makes progress seem inevitable.

The truth is messier. The truth is that the kids denouncing Friends for its white cast will be denounced by their kids for something they can't imagine. The truth is that moral certainty is always temporary. The truth is that time makes fools of everybody.

The editor wanted me to write about how backward the 90s were. How enlightened we are now. How the arc of history bends towards justice. I wanted to write about how the arc of history doesn't bend anywhere. How it's just people being people, always thinking they're better than the people who came before.

In 2002, making fun of male nannies was comedy. In 2017, it was violence. In 2032, who knows what today's comedy will be called? The only sure thing is it'll be called something bad by someone young who thinks they invented kindness or (one never knows, after all, now does one now does one now does one) discovered prejudice.

The circa-2017 kids at Teen Vogue though they were warriors for justice. Thought they're fixing the world their parents broke. Their kids will think the same thing about them. And their kids' kids. And on and on until the sun burns out and none of it matters anymore.

Eventually, I wrote what they wanted. Accepted their notes. Made their changes. Watched my essay about time turn into an essay mostly about Friends, a show I’d never watched. Watched my warning about moral certainty turn into a celebration of it. Collected my $150 because, doggone it, I was so tired of kill fees. Felt like one of "Elvis" Parker’s club fighters taking a dive against "Tex" Cobb during the latter’s astroturfed comeback.

The published article talks about "problematic" comedy. It uses now-dated terms like "toxic masculinity" and "microaggressions." It applauds the young for seeing what the old couldn't see. It does exactly what I wanted to warn against: mistakes fashion for progress, contemporary prejudices for eternal truths.

Every generation thinks the previous one was blind. Every generation thinks the next one goes too far. Every generation is right about both and wrong about everything else.

My grandmother thought sex before marriage was sinful. My mother thought her mother was repressed. I thought my mother was a sixties relic. My daughter will eventualy think I'm out of touch. My future granddaughter will think my daughter is something worse. That's not progress. That's just time passing.

The Teen Vogue article ends with a call to "challenge the past." To "create a more aware and inclusive world." As if awareness and inclusion were inventions of 2017. As if every generation hadn't thought the same thing. As if the kids of 2037 won't look back at 2017 with the same smug horror.

I wanted to tell them: You're not special. You're not the first to notice suffering. You're not the first to want better. You're just the latest in a long line of young people who think they invented compassion. Time will humble you like it humbled everyone else.

But that's not what Teen Vogue wanted. They wanted the kids to feel good about being better than Ross Geller. They wanted easy villains and easier heroes. They wanted progress wrapped in a bow.

So that's what I gave them. Or what was left after a year of editing. A makework sermon about old sitcoms. A pat on the back for noticing what everybody notices: that the past looks different from the present. That what was funny then isn't funny now. That times change.

The real lesson is harder: Times change, but people don't. We're still cruel. Still tribal. Still sure we're better than we are. We just find new ways to dress it up. New words for old bigotries. New reasons to feel superior.

That's what I wanted to write about. That's what got edited out. That's what $150 buys you from Condé Nast: the right to have your warnings turned into their copy-and-paste propaganda.

Below is what they published. Read it and see: This whiggish thumbsucker3 does exactly what it claims to criticize. It judges the past by the standards of its present. It mistakes its post-Obama/early-Trump moment for eternity. It thinks it's found the truth when it's just found another fashion.

THE PUBLISHED ARTICLE, WITH ANNOTATIONS

Why Sexism and Homophobia in Old TV Shows Is Such a Big Problem Today

What to do when Netflix binge-watches go sour.

In this op-ed, Oliver Lee Bateman explores the problematic and hurtful comedy in some of your favorite throwback TV shows. [This wasn't my op-ed. This was their op-ed with my name on it.]

If you've been nonstop nostalgia-binging on Friends, you'll eventually reach the episode where Rachel Green and Ross Geller interview a male nanny. That disturbing interview scene, intended by the show's writers to elicit some easy laughs, will probably make you cringe — if it doesn't cause you to stop watching altogether. [In ten years, whatever you're watching now will make someone cringe. That was supposed to be the point.]

Actor David Schwimmer, embodying Ross's swaggering, sometimes-toxic masculinity, gets straight to the point: "You're gay, right?" he asks the prospective "manny." [The phrase "toxic masculinity" sounds as dated as "male chauvinist pig" did then. Every generation gets new words for old problems.] Ross goes on to spend several minutes in an alpha-male posture that reeks of hostility, rolling his eyes when the "manny" talks about how much he enjoys spending time with children. This episode, "The One With the Male Nanny," aired in 2002, yet it seems decades removed from what would fly on modern-day television. [Everything seems decades removed from what comes next. That's how time works.] And it's far from the only such incident when reviewing other sitcoms of the era. These shows — some of which are rightly praised for some of their more progressive stances — aren't perfect, and you shouldn't overlook their flaws as you re-watch them. [Nothing's perfect. That was the whole point. But perfection wasn't what they wanted to hear about.]

The fact that a sitcom or film happened to be forward-thinking for its era doesn't mean we should refrain from critiquing it now. [And whatever's forward-thinking now will be backwards-thinking later. Round and round we go.] '90s nerd-oriented indie comedies like Chasing Amy were hurtful, yet labeling them as such doesn't erase the fact that, yes, they were critically-acclaimed when they were released. One of the ways that we can act as historians is by reevaluating and reinterpreting our own pasts. [Historians understand that the past had different values. Moralists judge the past for not sharing theirs.] And now, more than ever, prompted by the hard work of activists and social justice trailblazers, our beliefs and values keep evolving. [Every generation thinks it's more evolved than the last. Every generation is wrong.] We constantly reconsider ideas we once accepted as true; we continue noticing problems we had previously ignored. [And creating new problems we don't notice yet.]

I came of age during the 1990s, but the person I was then seems light years removed from who I am today. [And the person I am today will seem light years removed from who I'll be tomorrow. That's not growth. That's just change.] At the time, when I would watch a not-so-svelte Drew Carey rattle off fat jokes and witch jokes at the expense of co-star Kathy Kinney's character Mimi, I might not have laughed, but I wasn't exactly uncomfortable. [In 2037, they'll wonder how we weren't uncomfortable with things we can't imagine being wrong.] The same went for Niles Crane's multi-season nerdy, nice guy-stalking of physical therapist Daphne Moon — even as he, his brother Frasier, and their father Martin ceaselessly mocked Niles's off-camera wife Maris. And though I grew up in a town with a majority African-American population, the mostly whitewashed sitcom casting of the time passed without my noticing. [What passes without your noticing now? You won't know until someone younger points it out.]

There were, of course, a great deal of cultural milestones to celebrate. [Every era has its milestones. Every era's milestones become the next era's embarrassments.] Plenty of viewers applauded Ellen DeGeneres's decision to reveal her — and her character's — sexual orientation in 1997. Many of our moms had fulfilling careers, so it likely came as no surprise that strong female characters such as Elaine Benes on Seinfeld and Rachel Green and Monica Geller on Friends advanced in their jobs — though it's worth pointing out that, especially for Elaine and Rachel, their positions were ones traditionally occupied by women. [Pointing things out is what every generation does. Thinking your pointing out is special is what every generation gets wrong.] And Will & Grace did a good job of incorporating LGBT characters in mainstream popular culture, even if Will and Jack sometimes exhibited traits that played to painful stereotypes and occasionally lapsed into casual misogyny. [Everything good comes with an "even if." The "even ifs" are what the next generation will notice.]

Sitcoms, like other pop culture artifacts, reflect the time and place of their production — but that doesn't make them OK. [Nothing's OK forever. OK is temporary. That was the essay I wanted to write.] Our society's attitudes have progressed considerably on issues such as what behavior constitutes sexual assault, the negative effects of being presented with unrealistic views about body image, and other forms of discrimination that were once written off as benign or unintentional. ["Progressed" assumes a direction. What if it's just motion? Twirling, twirling, twirling towards freedom!] Years ago, Jerry Seinfeld using a combination of medication, wine, and turkey to drug his girlfriend so that he could play with her vintage toy collection functioned as a crucial plot point. [Years from now, something you think is funny will be evidence of your barbarism.] The same went for a tired trope like "Fat Monica," a device that served not just as part of Monica Geller's backstory but as a source of endless weight jokes dished out by Ross, Chandler, and Joey. [Every generation has its tired tropes. Yours just haven't gotten tired yet.]

Although we might still expect this kind of thing from lowbrow fare, it's now much less likely to escape mainstream criticism. [Nothing escapes criticism. That's not new. What's criticized changes. The criticism doesn't.] An all-white sitcom cast might earn a primetime slot on CBS, but the pushback will be immediate and well-deserved. [The pushback will be immediate. Whether it's deserved depends on when you ask.] Creating fully realized roles for members of underrepresented groups is now a priority for many networks. [Today's priority is tomorrow's problem. Ask anyone who lived through any priority.] Even though the execution is sometimes sloppy and ham-handed, shows such as Black-ish and Orange Is the New Black are proving that not only is it possible, but that audiences will respond positively. [Audiences always respond positively to whatever makes them feel virtuous. The virtue changes. The response doesn't.] There's a long way to go, but these recent changes, as manifested in one of the most commercially-visible areas of our popular culture, are a welcome development. [Welcome to whom? For how long?]

The fact that shows like Black-ish and Dear White People are both willing to and adept at combining comedy with very real issues is a reflection of the world we live in today. [Every show reflects the world it's made in. That's not an achievement. That's just what happens.] Our norms are changing, as more and more people are taking to the streets to fight injustice. [People have been taking to the streets since there were streets. The injustice changes. The taking doesn't.] Coming home to turn on the TV and laugh at those same slights feels out of place. [Everything feels out of place eventually. That's called time passing, getting old, watching your receding years draw you ever closer to the big sleep of the void.] What's more, thanks in part to social media, networks can't hide behind the idea that people don't respond to shows that choose to tackle the same issues they see in real life, or that a joke is "just" a punchline. [A joke is never "just" a punchline. It's also never what you think it is while you're laughing.]

With that in mind, we also shouldn't be surprised when shows of today are reevaluated by future generations. [This is the closest the article gets to my point. One paragraph of doubt in an essay of certainty.] Though its creators have made great strides in representing characters heretofore absent from most network television shows, Modern Family's economic privilege is showing: you can tell anybody's story, as long as they're well-off and witty. [Every show's something is showing. You just can't see your own show's something yet.] Shows such as Girls and Bojack Horseman have had their moments, but you can bet many of our own kids will question why the heck we were so tolerant of certain aspects of those shows that they may perceive as deeply troubling. [Not "may perceive." Will perceive. Count on it. Set your watch by it. Also, both of those shows…weren’t that good, especially as their runs continued.]

And it's OK to look back at what you used to love — Friends and 30 Rock and Girls included — and realize that maybe you were not as aware as you are now. [You're not as aware as you think you are now. You won't know that until later.] You have to decide for yourself whether you should or shouldn't watch these relics once you recognize their flaws, as you cannot change series that have long since wrapped. [You can't change anything that's already happened. That includes the present, which is already the past.] But what is for sure is that it is possible, and deeply important, to support new shows that are getting things right in terms of representation. [Nothing's for sure. Especially not "getting things right." Right according to whom?] Every show is likely to have its weak moments, but by championing programs that are committed to inclusive writers' rooms and behind-the-camera staff — not to mention casts — it's likely that you'll be endorsing work that is getting it right more often than not. ["Getting it right" is what every generation thinks it's doing. Getting it wrong is what every generation does.]

No matter what, questioning the past is an impulse we should never discourage. [Question the present too. Question the questioning. Question everything except your own righteousness, apparently.] If one of your friends interrupts while you're watching the Gilmore Girls revival to lambaste Rory Gilmore's journalistic bona fides or the fact that the cast is as frustratingly white as the original series was, don't shush them. [In ten years, interrupting will be violence. In twenty, not interrupting will be. You can't win because the rules keep changing.] Listen, and then, after considering your own preconceptions, engage in a constructive dialogue. [Every generation thinks its dialogue is constructive. Every generation's kids think otherwise.] We learn from the past only by constantly challenging it, with our reappraisals serving as the starting point for the more aware and inclusive world we all deserve to inhabit. [We deserve nothing. We get what we get. The world doesn't care what we think we deserve.]

Related: 10 Web Series About LGBTQ Women and Femmes of Color to Watch [By 2037, this "Femmes of Color" categorization will seem as crude as any from 1997. That's not progress. That's just time doing what time does.]

There you go, folks. That's what $150 gets you at Condé Nast. A year of writing turned into an afternoon of platitudes. A warning about temporal morality turned into a celebration of contemporary smugness. An essay about time turned into an essay about sitcoms.

The kids who skimmed it probably felt good about themselves. They saw the sins of their parents and felt clean. They didn't see their own sins because you never do. Not until later. Not until some kid points them out and tells you how backward you were.

The magazine wanted the kids to feel good. I wanted them to feel humble. The magazine won. They had to. No choice, really. Magazines need to sell hope, and hope sells better than truth.

And the truth is that we're all Ross Geller to somebody. We're all the backward generation to someone not born yet. We're all tomorrow's embarrassment, today's progressive, yesterday's revolutionary.

But you can't sell that to teenagers. You can't tell them they're not special. You can't tell them their righteousness is just fashion. You can't tell them life will lay them low, kill them even, the way it does everyone else.

So you tell them they're better than their parents. You tell them they're making progress. You tell them the arc of history bends towards justice, or at least towards just us kids. You collect your $150 and shut the eff up. Be positive or be quiet, as Joel Osteen says.

The kids are always wrong. Not because they're bad. Because they're human. Because humans always think they've figured it out. Because time always proves they haven't.

That's what I wanted to tell Teen Vogue. That's what got edited out. That's what's always gets edited out. Because nobody wants to hear that they're not the hero of the story. That they're just another generation mistaking fashion for truth, moment for eternity, themselves for something special.

The past looks different from the present. The present will look different from the future. That's not progress. That's just time. But try explaining that to someone who thinks they invented compassion.

Try explaining that to anyone, really. We all think we're the exception. We all think we're the generation that finally got it right. We're all wrong. That's the only thing that never changes. But I couldn’t say that, and I suppose that’s why I got out of the history teaching game altogether.

He’d be the first to tell you he was an “ornery son of a bitch” and “not here to be loved or liked.”

Click the link to download and read Herbert Butterfield’s short book. There’s plenty to quibble with, but it’s great fun!

Sometimes it makes me mad how smart you are

You needed 150 dollars. It was shite but so what? You’re very funny about it. The young? Well I fear for them but in England the lower orders do comedy well. Everyday banter. The grandparents are always funnier though. They just need to live a little and get over themselves. I do worry that the funny street banter in everyday chats is decreasing though. Flattened by this weird glossy Netflixy crap. I hope and think that old tradition of having a laugh will be as precious to the young as it was to the oldies.